As hundreds of nursing homes have shuttered in the last few years, the very strategies meant to prop up the sector have often left the most isolated, resource-strapped facilities with nothing gained.

Several new federal payment models and insurance programs are designed to allow skilled nursing providers to take on financial risk, tap into new revenue streams or access additional staffing and clinical resources.

But they have largely failed to take into account the unique conditions of rural facilities.

Rurals have fewer patients to attract needed payers to create needed critical mass for some new programs, for example. Additionally, they have a lower share of Medicare patients whose care is paid for at a higher rate.

And a staggering lack of physicians and clinicians needed to care for more medically complex patients also plagues isolated facilities.

“If you’re in an urban area, around 80% of a traditional skilled nursing facility’s [residents] are going to be long-term care and most long-term care, at least in the state of Oklahoma and many other states like Florida and Texas, they’re Medicaid,” explained Kimberly Green, chief operating officer of Oklahoma-based Diakonos Group. “They survive by getting those skilled patients in to get the Medicare Part A revenue. That sort of balances out so they can have some sort of margin there. In a rural facility, you don’t have that.”

Rural facilities’ Medicaid concentration is sometimes as high as 90% to 100%. That leaves little room for “extra” spending on staff recruitment, technology or additional clinical staff that could help them expand care and land more referrals for patients whose care is reimbursed at a higher rate.

A 2023 federal report found that state Medicaid programs covered as little as 62% of a nursing home’s per-patient costs, and 81% of nursing homes nationwide reported they were underpaid for the Medicaid care they delivered.

Medicaid penetration is generally higher in rural areas of a given state, and those beneficiaries are often older, poorer and sicker than those in urban areas, meaning their care may be more costly, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission.

Advocates argue that lack of fair funding creates a vicious cycle, one compounded by a lack of patients as demographics shift and many small towns get older and smaller. They also insist health disparities among rural seniors and the providers who care for them deserve the attention of policymakers and legislators, but to date, there have been few initiatives that either boost payments to rural nursing homes or support their goal of caring for a broader range of patients.

Meanwhile, accountable care organizations and specialized Medicare Advantage plans — seen as a potential financial lifeline by some in the sector — aren’t necessarily set up to attract plans into underserved and underresourced communities.

“Value-based programs are certainly the wave of the future for population centers,” acknowledged Nate Schema, president and CEO of South Dakota-based Good Samaritan Society. “What we’ve been challenged to see here as we operate in some much more rural communities is that the value isn’t the same in those communities when you’re serving a Medicaid population of at least 50 or 60%.”

“Low-volume locations are inherently at a disadvantage,” he added. “How do we maybe look at those payments or maybe equalize some of those payments?”

Lack of rural clinicians

For Mark McKenzie, CEO and founder of Focused Post-Acute Care, a lack of physicians and advanced practice clinicians to care for patients at his 26 Texas facilities is the most pressing issue. If the government would pay more for them to drive to and treat patients at his mostly rural facilities, he could work with hospitals to capture more of the locals being sent miles away from home for skilled care.

Nationally, the only physician add-on available, however, is for doctors associated with rural clinics, or those willing to create a clinic of their own.

“No physician’s going to do that for one patient. Delivery of healthcare and being reimbursed for healthcare as a provider should not be that difficult … but we make it difficult in our processes,” said McKenzie, who has for years lobbied lawmakers on the idea of a critical access label or “safety net” designation that sends more financial resources to rural nursing homes at risk of closure.

Those efforts, though, have gained no traction. In the meantime, McKenzie last year gave up five facilities he’d been operating to ensure that his company survives. He said he’s been part of several organizations that viewed their rural facilities as “loss leaders,” operating with little to no margin simply to fulfill a mission in a given community.

But with post-COVID inflation, that strategy has become too costly and threatens organizational livelihood. Good Sam, the nation’s largest nonprofit skilled nursing provider, last year announced it would scale back its operations to core states and has in some cases shrunk its operations even within that core footprint.

“I don’t think lawmakers understand rural healthcare in general, and I think when they hear us [skilled nursing operators] talk about the magnitude of the problem, they assume that we are crying wolf,” McKenzie told McKnight’s.

“We talk about how difficult it is, and then the same guy is there five years later talking about how difficult it is,” he explained. “The lawmakers want to know, if it was so difficult and dire and you were on death’s doorstep five years ago, how have you managed to make it today? I’ve been asked that same question, and at least two times, my answer was, ‘Well, the other three nursing homes in town closed, and I gathered all their employees and all of their remaining residents.’”

‘Paradigm’ shift needed

Rural providers are confronting a wave of closures but also know the advent of elderly baby boomers necessitates convenient care should remain for rural residents. While they might dream of broad policy solutions and reimbursement changes that could protect patient access, many would be open to smaller, simpler solutions.

For regulators at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, much of the focus of the last decade-plus has been on moving patients into value-based care arrangements. The models align pay with performance, but they’ve mostly been designed in a way where insurers flock to markets with a high number of Medicare beneficiaties to spread out risk and improve their chances of earning profits.

Nursing homes in general have been largely left out of those models, including, until recently, accountable care organizations that are typically focused on primary care. In an ACO, providers that meet performance goals and help save the Medicare program money bank a share of those savings.

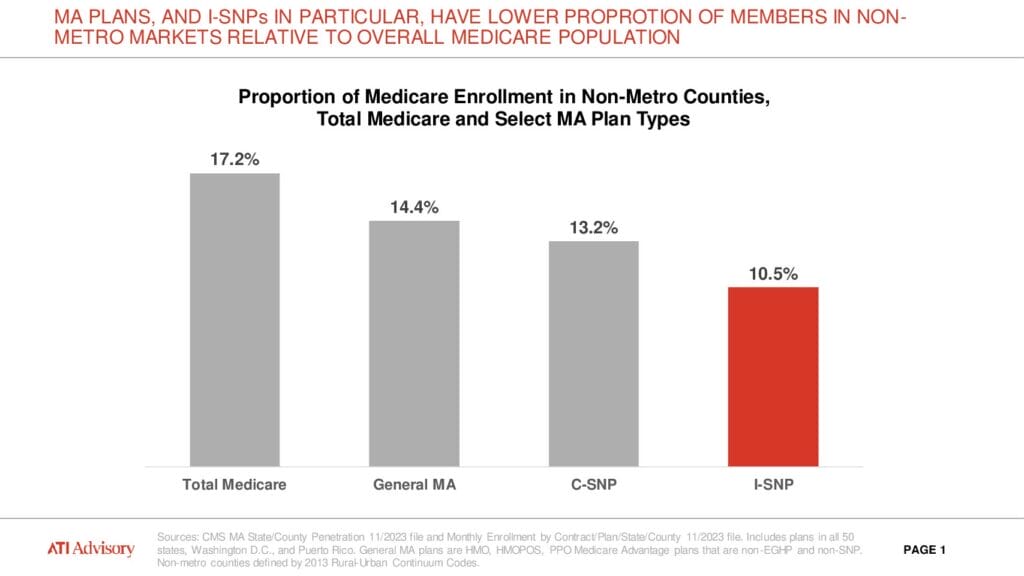

“As we see ACOs and this new long-term care ACO model starting to pick up, and Institutional-Special Needs Plans, we haven’t seen as much development in rural markets,” said Fred Bentley, managing director of ATI’s post-acute/long-term care and senior living practice. “So much of the I-SNP and ACO development is really driven by specialized health plans who are the ones going out and knocking on doors, and building up networks and building partnerships with these facilities. They’re driving this, and the question is: Can you get to a critical mass with rural facilities?”

ATI is working with a group of rural facilities to create a larger consortium that could better position the members to land value-based care contracts, but Bentley knows they might have to turn the tables and go knocking on the plans’ doors themselves. Insurers looking to grow in an increasingly competitive value-based care market, he said, recognize that they need lives just about anywhere they can get them.

And the National Association of ACOs seems ready to move. It acknowledges that too few rural settings are involved and this month asked CMS to refine how it provides incentives and rewards in rural markets for alternative payment models.

“We need a new paradigm where safety-net-minded APMs focus on increasing or maintaining access rather than purely reducing costs,” wrote President and CEO Clif Gaus. The group asked CMS to modify existing models with waivers that better account for safety-net populations or develop new ACO tracks focused on rural and underserved populations.

Special Needs Plans grow

In the meantime, some rural skilled nursing providers are making a run at risk-taking with I-SNPs offering special coverage and benefits targeting long-term residents of nursing homes.

Good Sam launched its Great Plains Medicare Advantage program about six years ago and has more than 1,000 members enrolled. Schema calls it a “key investment” in the future despite some “bumps and bruises in the early days of getting that off the ground.”

Tennessee-based American Health Partners has made it a core mission to target rural areas with its plans, which started in the facilities run by its sister company, American Health Communities. Today, it has about 7,000 beneficiaries in I-SNPs across 12 states with 35 joint venture partners — most of them in rural areas.

“Population health models are just much more difficult when it’s a disparate population in terms of being able to get them clinical resources,” said Hank Watson, American Health’s chief development officer.

“The nursing home population, they’re all in one place and we can really have a meaningful impact. Because of that, you can make investments in clinical programming even if the nursing home is only caring for 40, 50, 60, 70 folks at a time,” said Watson.“We were providing care to these folks 24/7 in rural settings already, and so the incentive just allows us to invest more heavily in that clinical model.”

In other words, the I-SNP can get around some of the volume problems other alternative payment models bring with them to rural markets. Still, plans have to very carefully figure out how to map travel times and allot resources, says Bridget Grover, vice president of TruHealth.

The company places nurse practitioners in American Health Plan-affiliated communities, and increasingly it’s being called on to float CNAs between the locations it supports. Those extra resources can amount to improvements in patient outcomes and quality of life. And the facility’s are able to earn a critical incentive when they prevent rehospitalizations.

“A big part of this is linking that clinical model to a financial model that pays the facility for the outcomes that they’re driving,” Watson added. “It’s a real key.”

Limited rural reach

Still, research conducted by ATI shows that I-SNPs represent a lower proportion of members in non-metro markets relative to the overall Medicare population.

Until that shifts or new models come to bear, providers will have to be creative in finding ways to help themselves, said Tyler Cromer, director of ATI’s complex care program, policy and research practice.

“It’s going to be hard to play the value-based care numbers game in a lot of rural places, because the numbers just aren’t there,” she said. “But we don’t want our rural communities to lose the assets they do have. If your building isn’t full, can some of that space be repurposed? Can some of that space be used for an outpatient dialysis clinic? Can a mobile primary care clinic come and park in the parking lot?”

Hospitals in rural locations, she added, are finding it especially difficult to discharge patients with behavioral health needs. Working with other community organizations to embed resources in shared spaces or finding a way to partner on specialty care could help keep doors open, but providers must be cautious about meeting regulatory requirements across sectors.

And outside of broad funding reform, smaller policy concessions might be easier to win from lawmakers or regulators.

Ideas for financial survival backed by operators and experts interviewed by McKnight’s include:

- Waive the 3-day stay requirement for rural providers seeking Medicare patients, as CMS widely did during the pandemic and continues to do for many Medicare Advantage plans;

- Create federally funded training programs or loan repayments programs that encourage more clinicians to support rural nursing homes (and other rural facilities);

- Fund state-level add-ons for what lawmakers deem critical access nursing homes, such as a past program in Pennsylvania that sent extra payment to rural, county-owned operations; and

- Support unrelated groups of nursing homes working together, whether to take advantage of group-purchasing or to create volume needed to participate in some programs.

“We’ve got to be creative and address the times that exist. I think the pandemic forced us to think differently, but we’re not finished dealing with the impact on the changes in our market,” said Shayla Higginbotham, principal and Healthcare Advisory leader at consulting firm CohnReznick.

She called for continued pursuit of a holistic, federal approach that recognizes how healthcare, medicine and food deserts are impacting the lives of already vulnerable rural residents.

“If you’re not witnessing the disparities of care in these areas,” she said, “you honestly do not have a true lens as to what needs to be addressed.”

This is the final installment of the Rural Peril series. Be sure to read about dwindling access, the role of staffing, and the need for technology investments here.