BLOOMFIELD, NE — Like many of its skilled nursing neighbors in the Cornhusker State, Good Samaritan Society-Bloomfield is teetering between fulfilling its vital community role with special small-town flourishes and succumbing to the financial pressures that come with operating in that same small-town setting.

For 60 years, staff here have encouraged the residents of Bloomfield to “come on up the hill” when they need long-term care or therapy or just want to visit with someone who does. But the community’s population — it shrank from 1,114 in 2000 to 987 in 2021 — means fewer potential workers and less opportunity for those who do live here to receive care locally.

The Bloomfield nursing home still garners many of its worker and patient referrals from neighbors bumped into at the nearby Country Market or over lunch at Misty’s Saloon, six small blocks away on a quintessentially small-town America street.

But there’s an increasing concern that those who need rehab or long-term care will end up going instead to facilities at least 30 miles away, even if many of those buildings are restricting admissions, too, their nursing ranks also decimated and leaders unable to recover from pandemic-era occupancy losses.

Meanwhile, many of the technology options that have helped metro-area nursing homes transform the kind of care they can provide still present hurdles for old buildings in far-off locations. And alternative payment models that have started to pump some much-needed staffing and financial resources into nursing homes in population hubs have in large part left rural nursing home operators out of the mix.

In addition, what staff can be lured to rural locales or from competitors in the same geographic regions — especially the travel or agency nurses needed to plug constant holes — are demanding pay that undercuts facilities’ long-term financial sustainability.

The leader of the nation’s largest nonprofit skilled nursing provider says access to post-acute and long-term care is at a ‘tipping point’ in rural America. While one-time Medicaid rate boosts helped stabilize some facilities in recent months, a single catch-up followed by years more lackluster policy or funding won’t keep doors open perpetually, Nate Schema, president and CEO of South Dakota-based Good Samaritan Society, told McKnight’s Long-Term Care News.

“All it takes is a few things to change, a few levers to be pulled, and I think that rapidly changes. We’re right on the edge,” said Schema, whose organization does 70% of its work on behalf of rural patients. “You have a finite number of people to pull from for workforce, and you’re serving such small numbers of people, but these are critical community care hubs.”

And while a better business model might net providers more patients in some locations, that isn’t necessarily an option in predominantly rural states.

“We’re not going to see this influx of Medicare rehab folks. You’re not going to see a brand new population come through on a commercial health plan,” Schema said. “It’s pretty straightforward. We’re out here serving these communities, and there’s just very little margin for error.”

A ‘death’ march for rural facilities?

The biggest lever of concern for many providers is the federal government’s planned staffing mandate, which virtually no rural nursing homes could meet, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ own estimates.

That proposed rule, Mark Parkinson, president and CEO of the American Health Care Association, said at a recent event exploring rural healthcare needs, is “literally a death sentence for nursing homes in rural areas.”

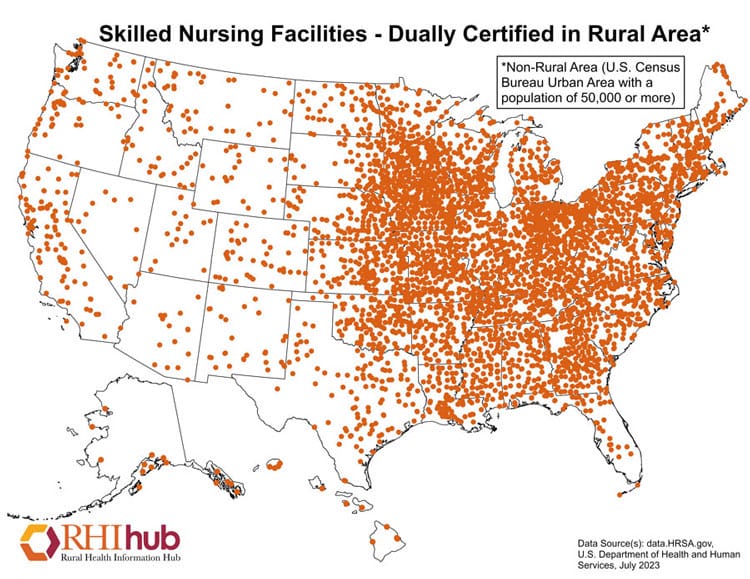

Rural nursing homes made up 31% percent of all nursing home closures since 2020, according to AHCA data. That rate peaked in 2022, with 37% of that year’s closures involving rural providers, even though 13.5% of the nation’s roughly 15,000 nursing homes are considered rural, according to the Office of Management and Budget.

In some places, the sheer numbers are astounding. Between 2000 and 2022, Oklahoma lost more than 100 nursing homes as its over-60 population exploded by 200,000 people, according to Care Providers Oklahoma.

But closures are occurring in all states with rural settings, making this much more than just a heartland issue. For instance, at least seven Maine nursing homes have closed since 2021, despite facilities there staffing at some of the highest rates in the country.

“Rural Maine is as rural as anywhere you’re going to get in the Midwest or the West,” said Robyn I. Stone, DrPH, senior vice president of research for LeadingAge. She’s also a board member of Pennsylvania-based Presbyterian Senior Living, which has its own rural holdings in a four-state East Coast footprint.

In areas with populations that are aging and shrinking at the same time, issues around access to care are quickly compounded, Stone added.

“When you’re in a state where all of the young people have left or just flock to the few magnet cities, then you’ve got a much more significant challenge because you’re left with an over-representation of older adults,” she said. “Sometimes, yes, there’s a nursing home still in the community. But a lot of times they’ve closed and then if somebody needs a nursing home, there’s no alternatives for home care. They have to go very far away to go to a nursing home. … When these places close, it’s even worse because they don’t have any options.”

Case study in looming closures

It’s a nightmare scenario that Administrator Madison Ternus thinks of often as she does her 8 a.m. rounds at GSS Bloomfield, greeting each resident by name and checking in with her crackerjack staff.

To mark her first year at GSS-Bloomfield, Ternus was gifted a crushing staffing collapse that required her and her director of nursing to cover nearly every shift to ensure continuity of care. At the time, she feared the facility might have to close its doors, and that fear returned with a vengeance when she learned about the CMS staffing proposal that was unveiled in September.

“I’m going to do everything in my power to make sure it doesn’t close, but when you put out this proposed mandate, you can’t help but to think about it, and to think about where these people would go,” said Ternus, 22, who moved to a small farm outside Bloomfield to train at the nursing home. “Everyone knows everyone here. They’re my family. I see them every single day.”

Fears have turned to reality in many communities already. Strangled by staffing shortages amid lagging Medicaid payments, 15% of Nebraska nursing homes have closed since 2018, said Kierstin Reed, CEO of LeadingAge Nebraska.

“Our losses here started before the pandemic did, and most of that was due to cost of care and the Medicaid rates not being where they needed to be,” Reed told McKnight’s, noting a drop from 217 [facilities] to 187, with the majority of closures in rural areas and in the state’s sparsely populated western two-thirds in particular.

Sixty of the state’s 93 counties have two or fewer nursing homes. Another 18 have none. That includes Cherry County, which boasts a population of about 5,500 spread over 6,000 square miles. It has a lone assisted living facility to care for seniors, according to Reed’s data.

Plenty of other residents may be facing similar conditions but have no idea that their cozy, quiet nursing home may have to shut its doors if it’s only filling 40% to 50% of its beds for months on end. Reed estimates 80% to 90% of her members are limiting admissions due to staffing, self-limiting their occupancy rates and their opportunity to cover their fixed costs.

A place for everyone

Admission limitations can change by the week at GSS-Bloomfield, which is licensed for 70 patients. After finally hiring late last summer, the facility hit 30 residents — a level not reached for the past three years.

Sometimes, Bloomfield is helped when other facilities suffer the same staffing impossibilities. “Full” buildings in Lynch, an hour away, or Yankton, SD, on the other side of the Missouri River 30 miles to the North, also are operating undercapacity, sending a trickle of patients to Ternus and her team.

Back down to 26 patients when McKnight’s visited last fall, Ternus offered an optimistic-but-realistic outlook. She knows that among the recent Nebraska closures were at three buildings operated by Good Sam.

The organization has raised pay, boosted benefits and otherwise tried to make nursing home jobs more attractive. But the same issues dogging Bloomfield are rampant in the sector, and some jobs have remained open not for months, but for years. In October, Ternus was advertising six openings, including day-time and overnight shifts to try to open more beds.

“It’s tough to get people in here, but everyone needs a place to be,” she said, noting that her workers also need an employer, given that there aren’t many in the area.

Industry advocates have been sounding the alarm on the loss of facilities for years now, but that hasn’t necessarily made the issue any more visible to the public or some lawmakers who control nursing home policy and funding.

“When’s the last time you went down to your local coffee shop and somebody brought up the idea of the nursing home? Nobody really hears about this until they need care,” said Larry Lester, a principal at consulting firm Wipfli in Eau Claire, WI.

“People are always amazed how difficult it is to access the care that they’re looking for. … When they can’t get admission because of staffing or the person’s needs, they’re really surprised. And then they’re really outraged by it,” added Lester, who specializes in reimbursement, financial forecasting and budgeting for nursing home clients.

“Until people actually need nursing home services, it’s not on anybody’s radar to really worry about it,” he continued. “That’s what scares me about the baby boomers: All of a sudden this group of people are going to age in place and need services and we’re going to say, ‘Where are they going to go?’”