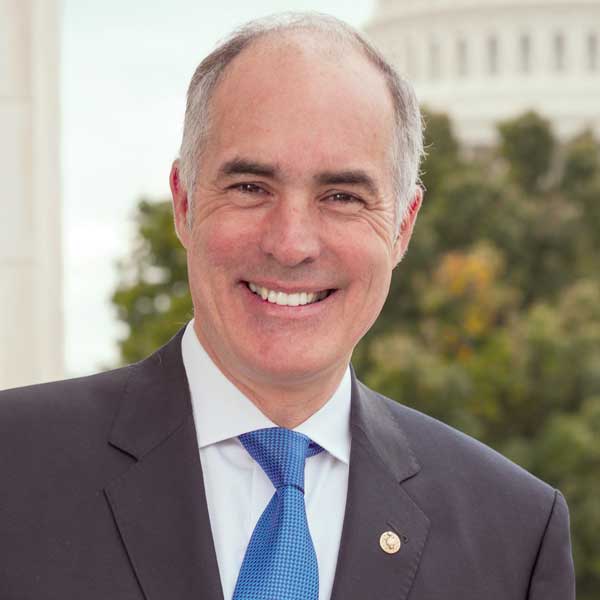

Sen. Bob Casey Jr. (D-PA) is demanding state survey agencies report information on extensive delays, staffing shortages and other challenges in the nursing home inspection process.

In a letter sent to all state survey agencies Monday and shared exclusively with McKnight’s Long-Term Care News, Casey said the inspection workforce was down by as much as 50% in some states. Surveyors, he noted, “drained by physically and emotionally demanding work,” have left the field in extensive numbers since the pandemic’s start.

As a result, 4,500 nursing homes were overdue for annual standard surveys, according to mid-August data provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

“State surveyors are the eyes and ears ensuring quality care is delivered,” Casey wrote. “Given their critical role, I am requesting information related to your agency’s staffing needs as the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging seeks to better understand the scope and severity of staffing shortages affecting state survey agencies’ ability to carry out their work.”

As chair of the aging committee, Casey has been an outspoken advocate for improved nursing home care and regulatory oversight. He told McKnight’s Monday that state survey agencies “keep people safe by conducting quality, consistent oversight at long-term care facilities.

“When their work is repeatedly delayed and interrupted, nursing home residents lose an important backstop looking out for their safety and wellbeing. I’m seeking information from state agencies across the U.S. to get a clearer picture of how far the issue of staffing shortages goes and how it may affect nursing home quality.”

Early in the pandemic, Casey played a key role in securing an additional $100 million of funding for survey and certification activities during the pandemic. In May, Casey warned CMS to shore up its enforcement practices, noting that one in five nursing homes in the Special Focus Facility program were overdue for inspections. The interval for those facilities should be every six months.

But state agencies that provide oversight functions for CMS also have struggled to keep up with the 15-month cycle required at the rest of the nation’s 15,000-plus nursing homes.

1,021 days between surveys

What had been sporadic delays became systemic in spring of 2020, as CMS stopped routine inspections. The time between surveys ballooned during the pandemic, when access was limited, and that was further bloated by a temporary focus on infection control surveys meant to improve pandemic responses.

At the end of May 2021, 71% of nursing homes had gone at least 16 months without a standard survey, up from 8% in June 2020, according to a January 2022 report from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Inspector General.

On Monday, the nationwide average was still at 16 months, but many states were seeing far greater lags according to an analysis of a national database, Melanie Tribe-Scott BSN, Zimmet Healthcare Services’ director of Quality Initiatives, told McKnight’s.

Maryland is leading the nation at 1,021 days, or about 34 months between standard surveys, followed by Idaho at 999 days and Kentucky at 900.

In worst-ranked Maryland, the Department of Health’s Office of Health Care Quality is working closely with CMS to provide oversight of nursing homes, spokesman Chase Cook told McKnight’s.

The Office implemented a staffing plan to address overall needs, including in the long-term-care unit. It allowed for controlled growth of 5 to 6% increase in workforce, with 10 new positions added in state fiscal years 2018, 2019, and 2021. An additional 10 were received this July, with hiring to continue next year, too.

“OHCQ also implemented multiple strategies that enhanced recruitment and retention efforts,” Sook said in an email. “These included a new office location, user-friendly onboarding process; long-term employee mentoring program; increased opportunities for career advancement; leadership development programs; and increased pay for certain job classifications.”

Pennsylvania and New Mexico, meanwhile, are among the most timely survey takers, Zimmet found.

“Providers are relieved that they can finally catch a breath from all the focused infection control surveys, but are anxiously awaiting the standard survey,” Tribe-Scott said. “This delay could greatly impact the Five Star Health Inspection rating, which takes into account the last three standard surveys. In other words, if a facility is late for a standard survey, then a bad survey from five years ago or longer could still be reflected on the Five-Star Rating.”

Delayed surveys also limit the opportunity for oversight and slow the flow of information on current performance metrics used by consumers. Casey has argued on behalf of increasing funding permanently — a quest taken up by the Biden administration in its nursing home reform plan. The president called on Congress to provide an extra $500 million, a 25% funding increase, to CMS to support nursing home inspection activities.

‘Widespread’ nurse shortages contribute

The January OIG report found staffing shortages were “a root cause of state survey performance problems, adding that ‘many of the staffing shortages occur in states with widespread nurse shortages and that these states have difficulty attracting and retaining nurses to conduct surveys.”

Conditions appear not to have changed, despite warnings from CMS and others about the need to return to routine surveying.

Casey said CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure told him in a July letter that “many states have reported ‘shortages that impact their ability to respond timely to complaints and recertification surveys’ an issue exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Casey’s letter pointed out that state survey agency officials across the country are reporting challenges with hiring and retaining surveyors, particularly nurses who make up the majority of their workforce. Some states, he wrote, have seen shortages of up to half their budgeted positions, forcing states to call in contractors and further extend the time between standard inspections.

Many state survey agencies have continued to rely on what Casey described as “stopgap measures” amid a nationwide nurse staffing crisis. Tactics include hiring pricey contract inspectors; encouraging in-house surveyors to work overtime; hiring back retirees and spreading surveyors across larger regions.

Meanwhile, workloads increased substantially, with the number of inspections in response to reported complaints increasing from 47,000 in 2011 to 71,000 in 2018, a trend that Casey said had continued during the pandemic.

“State officials and outside observers have expressed concern that a strained workforce is not well-suited to carry out the critical work survey agencies perform, leaving nursing home residents at greater risk,” Casey wrote.

History of delays

The OIG and Government Accountability Office have repeatedly linked survey agency staffing shortages with failures to conduct timely, high quality nursing home surveys, Casey wrote. Survey agency officials, he said, “repeatedly voiced concerns regarding state and federal budget shortfalls and difficulty offering competitive wages in a highly competitive healthcare market. Over the last decade, nursing salaries have increased 21 percent.”

Now that many states are experiencing surpluses, it’s unclear how many are offering higher pay to attract more surveyors or are willing to build that permanent expense into their budgets.

Casey is seeking specifics on how each state has been impacted by survey turnover; the reasons workers are leaving; and how the nationwide nursing shortage may be “challenging their ability to hire and retain nurses as surveyors.” He is requesting information about pay increases, schedule changes or other incentives, as well as how surveyor salaries compare to those for registered nurses in other positions in a given state.

He has also asked for information on the use of contractors to fill surveyor vacancies and address backlogs and conduct tasks such as informal dispute resolution. The committee will review five years worth of contracts from each state and work to understand how contractors are overseen by state health officials.