When a major government watchdog blasted the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in January for a lack of timely survey activity, it detailed extensively what providers on the ground were experiencing — or more accurately, not experiencing.

“We know the surveyors are late,” said Melanie Tribe-Scott, RN, RAC-MT, director of quality initiatives for Zimmet Healthcare Services Group. “Facilities know they’re really, really late.”

Although some states have a history of extending standard surveys beyond the 15 months expected by federal regulators, Tribe-Scott calls the stats of the last two years “mind-boggling.”

As of May 31, 2021, 71% of nursing homes had gone at least 16 months without a standard survey, up from 8% in June 2020, Tribe-Scott notes.

More than half of states repeatedly failed to meet nursing home survey requirements over a four-year period, according to the Office of Inspector General. This was most often due to a lag in conducting high-priority complaint surveys or standard surveys.

Those delays were compounded by COVID shutdowns and a temporary shift toward Focused Infection Control surveys. But even after CMS in November directed state agencies to resume standard surveys, routine recertification activity failed to materialize in many parts of the country.

A February analysis by consultancy firm Formation Healthcare found 5,249 facilities — or 34% — had still been waiting more than two years for a standard survey.

Early 2022 doesn’t look like it’s on track for an immediate rebound. Among surveys of hundreds of Formation clients through early February, 52% were complaint investigations, 26% were infection control surveys, 11% were fire safety surveys and 11% were annual surveys.

“It’s definitely survey agencies catching up from their backlog and having to prioritize some of those (complaints) depending on what the allegation is,” said Formation Managing Partner Jessica Curtis. “It’s probably a combination of the number of complaints that they need to go investigate, along with the staffing issues that I’m sure are affecting state agencies as well.”

Observers say the implications of missing surveys stretch from consumer confusion to extended admissions restrictions. It also can have profound implications in the lending universe, where potential financing may be a lot more expensive to providers with a poor survey they’ve been unable to have updated.

“They’re trying to climb out of a hole if they’ve had a poor survey,” said Spencer Blackman, product director at data analytics firm StarPRO. “They’re trying to recover (and) they’re looking for a new standard survey to make sure they have a chance to rise.”

Nerves fraying

With little clarity around when that’s going to happen, anxiety has been building.

“Data derived from a survey reflects a snapshot in time — what’s happening in a nursing home over four or five days,” said Janine Finck-Boyle, vice president of regulatory affairs for LeadingAge. “So for residents, families and providers, that information is most meaningful while still fresh. … If a survey is delayed, information about a provider is incomplete or inaccurate. That’s a problem.”

LeadingAge has conveyed to CMS its members concerns’ about late surveys, including a lack of timely follow-up visits needed to confirm whether operators have corrected past problems by a designated deadline.

Fines up

Delayed surveys are compounding the pain of citations, too. Average fines were up 64% in data published in the CMS December refresh and cited by Curtis.

“It’s very clear that they’re coming down with a heavy hand on the enforcement side,” Curtis said. “The change from the per-instance fines that we saw under the previous administration back to the per-day fines as a default is resulting in some very heavy fines and past non-compliance fines that are really adding up quickly.”

That makes internal documentation of corrected actions all the more critical for providers waiting on a follow-up survey to indicate a return to compliance. For those who continue accepting residents during a discretionary denial of payment for new admissions, a delayed survey that results in still-unmet corrections could be financially devastating.

And when surveyors are late, providers also need to be ready for a longer look-back period, Tribe-Scott adds. Facilities Zimmet works with have reported reviews extending to their most recent survey, which could have been two years ago.

“It puts the facility more at risk for having more citations during that time frame,” Tribe-Scott said.

Not enough to catch up

Of course, no one outside a nursing home can understand what’s happening in real time if fresh survey data just doesn’t exist.

CMS has five remedies to address inadequate state survey performance, ranging from providing training to scheduling surveys for states to instituting corrective action plans. The OIG found that CMS had already issued corrective action plans in half of the problem cases tied to survey timeliness; they did little to move the needle.

State agencies repeatedly cited staffing-related problems as a major contributor to falling behind. In Colorado, for example, 15 of 47 surveyor positions were vacant during the OIG study timeframe. State officials cited long hours and low pay as causes for resignations. One consultant told McKnight’s that at least one nursing home in that state was approaching three years without a standard survey.

Such complaints have drawn the attention of Sen. Bob Casey Jr. (D-PA), who had hoped to reform the survey process through a bill attached to the now-defunct Build Back Better package.

CMS response

CMS did not respond to several requests for comment from McKnight’s.

But CMS told the OIG that survey staffing shortages overlap states with widespread nurse shortages, exacerbating recruitment. In one state, the staffing situation “was so problematic” that CMS provided additional funding for new surveyor positions.

Tribe-Scott suggested CMS consider a collaboration with other Health and Human Services agencies or use vendors with relevant expertise to help state agencies tackle the backlog.

CMS can also impose sanctions or slap states with financial penalties.

The agency, in a memo to state agency directors earlier this month, reiterated the importance of timely and complete surveys, threatening to recoup budgeted money or send outside contractors to states that fail to meet their obligations.

Whether that happens — and whether CMS or anyone has the manpower to follow through — remains to be seen. Meanwhile, providers must stay vigilant for surveys that could come tomorrow or in weeks or months.

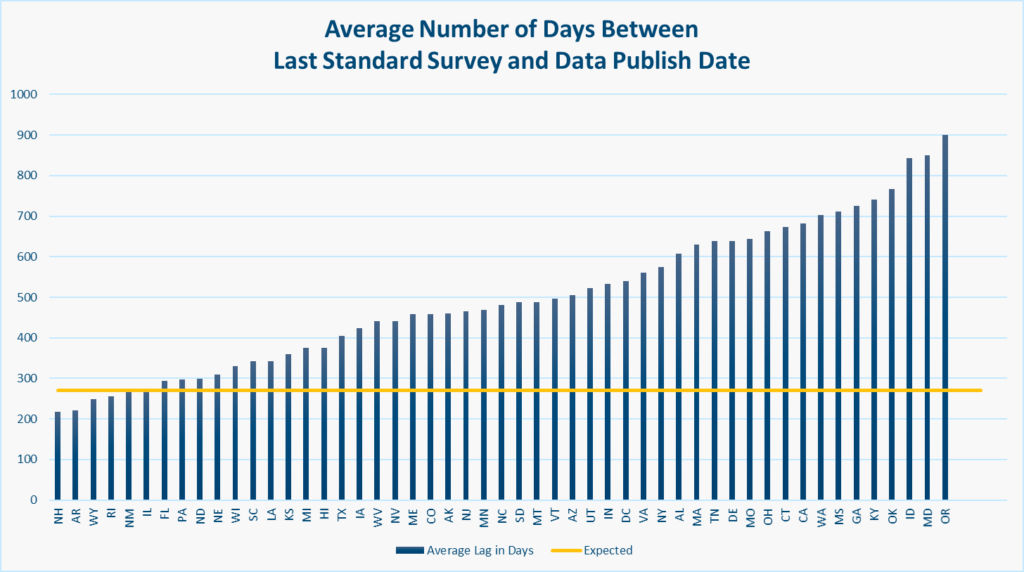

As of January, StarPRO data showed the average standard survey was about 500 days old. Pre-pandemic, the average was closer to 270 days.

State by state, there are wide variations. In Oregon, the average number of days between the last standard survey and a January data publish date was at 900, according to a StarPRO analysis. By January, only four states were doing better than the “normal” goal of 270 days.

“They fell behind quite a bit throughout 2020, and they haven’t really done a great job of recovering,” notes Blackman. “It’s trending in the right direction, but they’re still not really getting it done.”