Our brains are smarter — and more resourceful — than we may realize, according to new evidence.

Investigators of a study published on Feb. 6 in eLife found brains can pull in other areas to assist with brain function in order to compensate for age-related impairments. When the brain recruits these other areas, it can maintain cognitive performance.

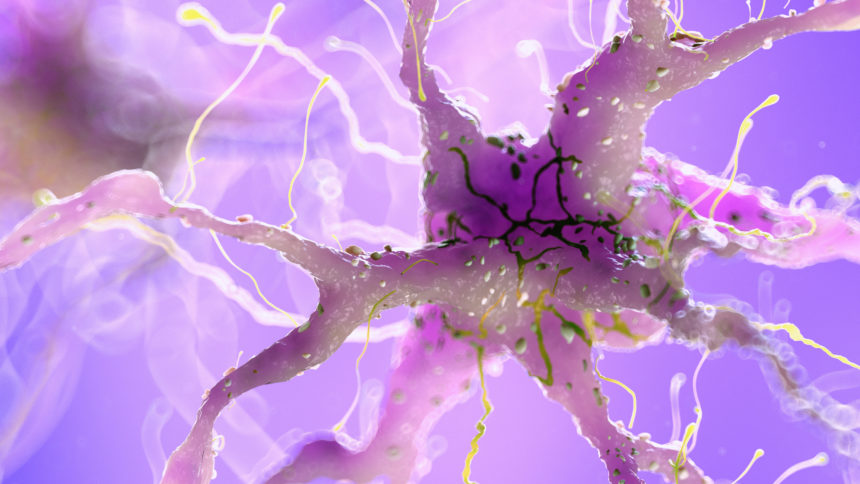

Scientists aren’t sure why some people have better brain function as we age. During the aging process, the brain’s nerve cells and connections decrease and brain function can decline.

Tasks can utilize the multiple demand network of the brain, which involves the front and rear areas. But activity of the network decreases with age.

“Our ability to solve abstract problems is a sign of so-called ‘fluid intelligence’, but as we get older, this ability begins to show significant decline. Some people manage to maintain this ability better than others.” Kamen Tsvetanov, a researcher at University of Cambridge and lead author, said in a statement.

“We wanted to ask why that was the case — are they able to recruit other areas of the brain to overcome changes in the brain that would otherwise be detrimental?”

The team from University of Cambridge in collaboration with the University of Sussex examined data on 223 adults from 19 to 87 years of age. The people had to spot the odd one out in a series of puzzles of varying difficulty while lying in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. During that time, the researchers observed patterns of their brain activity and measured changes in blood flow. It was harder for older people to solve the problems, in general. But the network was active, as were areas of the brain that process visual information.

The team noticed that two areas of the brain showed more activity in the brains of older people — the cuneus at the back of the brain and a region in the frontal cortex. Activity from those areas was linked to better performance on the task. Of those, only activity in the cuneus region was related to performing the task more strongly in older adults compared to younger people. The cuneus had extra information to do the task beyond what the network provided.

The team isn’t sure why the brain recruited the cuneus to complete the task; that area is good for helping us focus. Older adults often have a harder time briefly recalling information that they recently saw, such as the puzzle used in the task. Investigators think the increased activity in the cuneus might reflect a change in how often older adults look at the puzzle pieces as a strategy to make up for weaker visual memory.

“This new finding also hints that compensation in later life does not rely on the multiple demand network as previously assumed, but recruits areas whose function is preserved in aging,” added Alexa Morcom, another team member from the University of Sussex.