A new study of a key COVID-19 waiver backs up longstanding concerns that removing a hospital stay as a requirement for Medicare-covered nursing home care would shift too many long-term residents to skilled care coverage.

Research published Tuesday in JAMA Internal Medicine follows a recent report by a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid official that the 3-day stay waiver was often used to shift Medicaid patients with chronic conditions onto higher-paying Medicare rolls during the pandemic. While the majority of those patients had COVID, a finding confirmed in the JAMA study, CMS data raises questions about the motivation and cost of shifting those who did not.

The waiver removed the need for beneficiaries to have a prior 3-day hospital stay to trigger Medicare Part A coverage. It was used the most by skilled nursing facilities during the pandemic. It is expected to expire with the end of the public health emergency May 11.

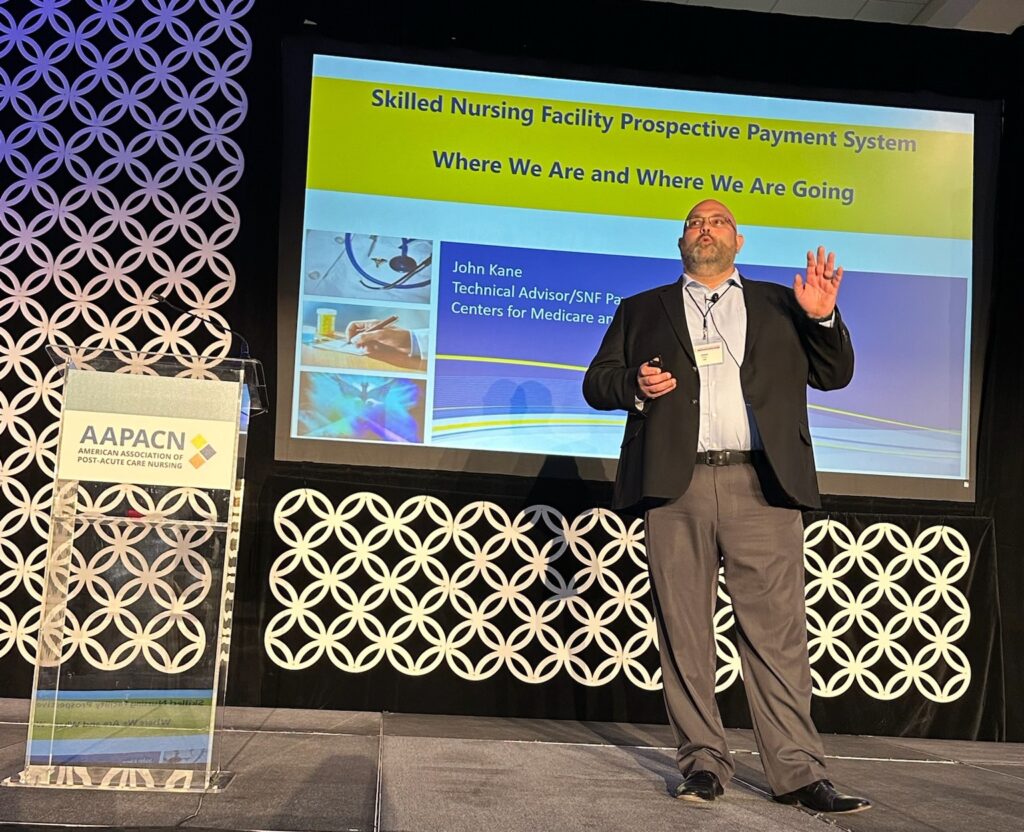

Previous Congressional Budget Office estimates have found removing the 3-day stay requirement could increase the cost of SNF care by $60 billion over 10 years, CMS SNF lead John Kane said while speaking at the American Association of Post-Acute Care Nursing (AAPACN) conference Friday.

While Kane said that skilling-in-place is a great tactic for patients who need more complex care, he added that regulators and lawmakers worry about the long-term implications of removing a requirement for a hospital stay for all beneficiaries.

The JAMA study, while demonstrating that the waiver worked to increase access during the first two years of COVID, appears to confirm those fears, at least in part.

Average monthly Medicare Part A spending on SNF episodes fell from $2.1 billion before the PHE to $2.0 billion during the PHE. That represented an average relative monthly spending decrease of 3%. But that decline also happened as nursing homes were seeing significant declines in occupancy.

And among long-term care residents, monthly SNF spending increased from $301 million to $585 million for a relative increase of 94%.

Hospital savings counter costs

Still, monthly Medicare spending on SNF care for long-term care residents was on average less than half (45%) of the spending on hospitalizations before the public health emergency began.

“While monthly spending on SNF care increased during the PHE, mostly during the peak months of COVID-19 prevalence, spending on hospitalizations remained more stable so that monthly spending on SNF care was on average 88% of spending on hospitalizations,” wrote researchers from Harvard and Washington University in St. Louis. “In contrast, the spending on a single SNF episode or a hospitalization remained relatively stable from 2018 to 2021. Total spending and per-episode cost remained stable for emergency department visits and observational stays through 2018 to 2021.”

The study reviewed the SNF stays of nearly 4.3 million Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries between January 2018 and September 2021. Overall, researchers found waiver episodes without a preceding acute care stay increased from 3% to 18% during 2020 and 2021. Among long-term care residents, such waiver episodes increased from 4% to 49%, with 62% of episodes provided for residents with COVID.

But in his comments last week, Kane explained that CMS had seen evidence that providers also used the waivers to move some patients with chronic conditions from Medicaid covered stays to Medicare ones. Among examples he shared at the AAPACN conference, Kane noted that the agency had seen a pattern of non-COVID patients diagnosed primarily with type 2 diabetes (without complications) waived into skilled stays.

“We’re trying to understand that population,” Kane said. “We have people that are being admitted under the QHS (waiver) memo. Where are those people coming from? Are they coming from the community? Are they coming from a hospital stay that simply lasted less than 3 days? Or are they being shifted from the long-term care side to a Part A stay?”

For certain non-COVID diagnoses, Kane said, 100% of patients had been waived into skilled care from facilities’ long-term care populations.

And the JAMA researchers, led by Harvard Medical School’s Agne Ulyte, MD, PhD, found that for-profit nursing and those with lower overall and staffing star ratings used the waivers most often.

Moderating effect offers alternative view

But in accompanying commentary, noted Brown University health services researcher Vince Mor underscored the researchers’ finding that conversions of long-stay residents into skilled care “moderated considerably” after vaccinations began.

That “suggests that general criteria of clinical need were being applied appropriately” by nursing homes, Mor wrote. He argued that the study is a good reason to reconsider the necessity of a 3-day stay, which is opposed by many skilled nursing providers and consumer advocates.

Most Medicare Advantage plans don’t require a 3-day hospitalization, and many accountable care organizations also have received permission to waive it. A CMS analysis published in February found that ACOs waiving some acute stay requirements didn’t see more bad patient outcomes or longer nursing home stays.

“The decades-old concerted effort to reduce incentives to hospitalize older individuals and those with frailty, such as NH residents, may have made the 3-day stay requirement obsolete,” Mor wrote. “Updating and extending the analyses reported by Ulyte and colleagues into the period until the public health emergency is withdrawn in May or June of 2023 is something we should anxiously await.