HOUSTON — One of the nation’s top economists predicts many of the workers who left the economy over the last few months may soon start returning, but that’s not all good news for an industry such as senior care, which has been hit by staff shortages and inflationary costs.

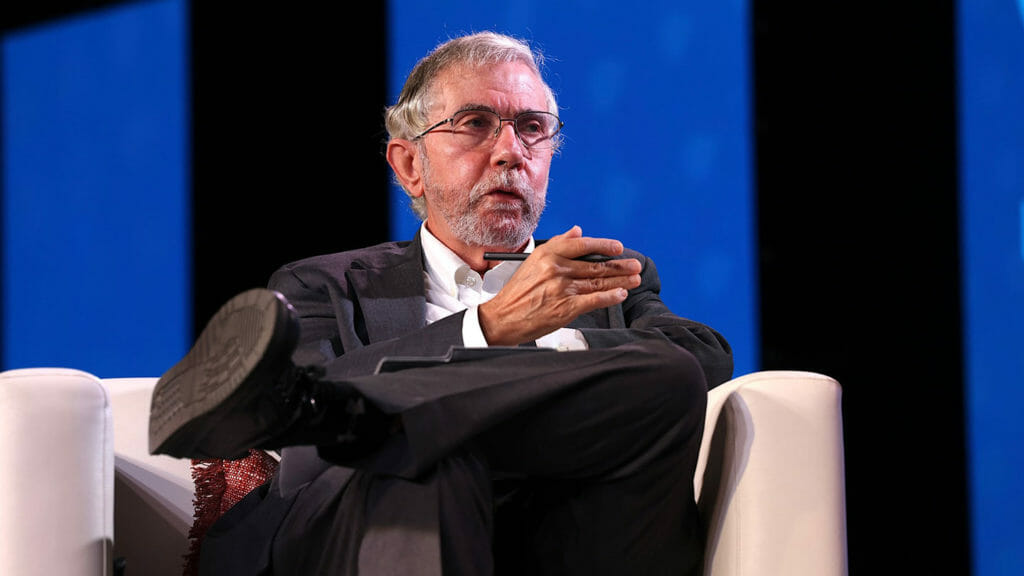

“The cash reserves that lots of people built up during the period of the pandemic have made it easier for people to be choosy,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman said Tuesday. “But those cash reserves are depleting as we speak. And so, we probably are going to see some increase in labor supply.”

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers joined Krugman for a standing room-only dissection of inflation, labor and policy issues at the NIC Fall 2021 Conference.

Summers said he is less optimistic that there will be a major increase in the labor supply, short-term. In addition to a Labor Department report that 4.3 million Americans quit the workforce in August, Summers said he was discouraged by data showing that millions more recently had been diagnosed with anxiety or depression while others sought early retirement during the pandemic.

Even if workers do come back, they could fuel a continuing cycle of cost concerns.

“We are looking at an economy with a record level of vacancies, with a record level of workers quitting, and with near-record low real interest rates,” said Summers, calling those factors combined with current federal fiscal policy “a prescription for inflation staying at problematic levels.”

More workers with more spending power will likely push the costs of consumer goods and services higher, and Summers and Krugman both warned that some inflationary effects are just beginning to emerge. Higher employment could “bake in” and make permanent what many have assumed is transitory, or short-term, inflation caused by COVID-19 and supply-chain issues.

“We’re four months into this period of (economic) overheating,” Summer said. “The inflation dynamics are likely to get worse over time.”

But Krugman took a different view, likening current conditions to the Korean War period when non-supervisory wages spiked 12% but then “faded away quickly.”

“It was a very real but very temporary phenomenon, and that is still my preferred story about how this is going to play out,” he said.

The top 3 issues

Nationally, about 6.6% of non-farm jobs are open currently, just shy of a 7% U.S. record. An early fall survey by the American Health Care Association found nursing homes to be especially hard hit. Only 1% was fully staffed, with 58% limiting admissions because they didn’t have enough workers to care for residents.

In a later conference session Tuesday, NIC President and CEO Brian Jurutka called labor the “No. 1, 2 and No. 3 issue that’s facing our industry.”

Mark Parkinson, AHCA’s president and CEO, said some specific policy actions and tools — including a temporary nurse aide training program that brought 200,000 nurse aides to long-term care — have helped. But he and the leaders of several other provider organizations said they also continue to pursue immigartion reform and restrictions on staffing agency tactics as a way to fill jobs and limit wage-related expenses.

“Unfortunately, there is no single, silver bullet solution,” Parkinson said.

One solution backed by Krugman: higher vaccination levels both in worker-strapped sectors and in the general population.

“Fear of COVID is still a factor out there. If you look at where shortages are greatest, they tend to be on frontline, exposed jobs,” Krugman said. “The biggest single solution to everything that’s going on is vaccination. As more people get vaccinated, people become more willing to consume services and people get more willing to supply services as well.”

The hits keep on coming

Summers expects those who have tried to avoid wage increases will soon be forced to increase pay. As wages are pushed up, more people are going to decide they want to work at those rates, and employers will have to find ways to economize.

He said many resistant employers are now realizing their efforts to attract candidates with interview, sign-on or retention bonuses aren’t cutting it.

“That stuff is kind of running its course,” he said. “There are a lot of people who are saying, ‘We needed to do all that. Now, we’ve kind of done it, and it’s not enough. Now, we’ve got to raise wages.’ ”

That tactic has likely led to “big delays” in the wage-setting process, meaning that employers may only now begin paying higher rates to current employees and new hires in a broad way.

“I think we’ve got a bunch of transitory, not-manifested inflation because the pressures we already have are going to show up in wage inflation down the road,” Summers said.

He also expects that broader expectations about inflation could push rates even higher and affect labor negotiations, noting that workers who see Social Security set to increase by 5.9% for 2022 might expect similar on-the-job treatment.