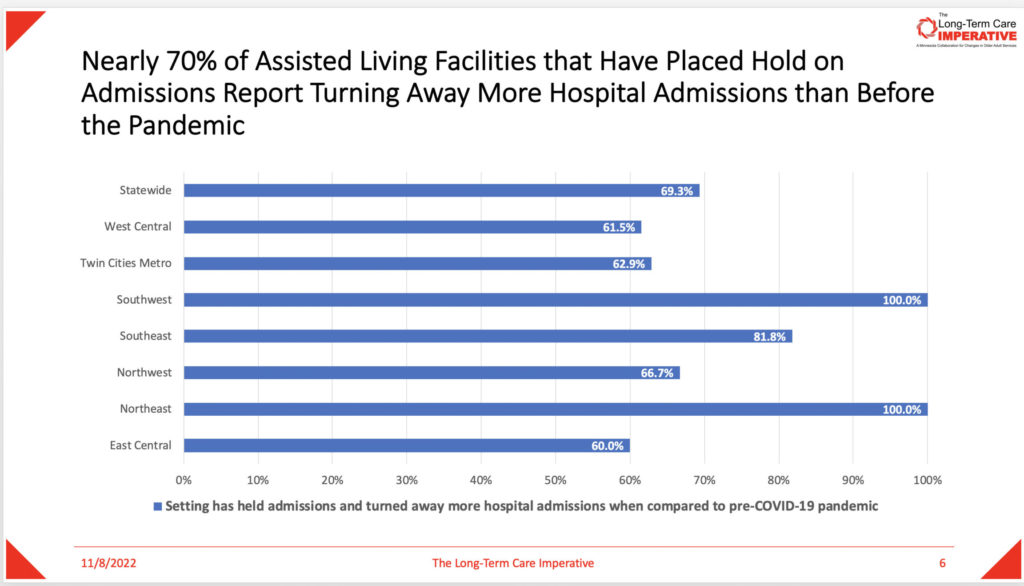

Minnesotans’ access to long-term care is low. Most of the state’s nursing homes are turning away new admissions, according to a recent analysis by LeadingAge Minnesota’s Long-Term Care Imperative.

Its survey, which collected data earlier this month, showed data point after data point reflecting the damage done by the pandemic and staffing shortages. Among the results from the 163 nursing homes responding:

- 4 of 5 have placed a hold on admissions during the pandemic

- 7 of 8 regions showed 90% or above of facilities that put holds on admissions turned down more admissions from hospitals than before the pandemic

- More than one-third of all the nursing facilities reported turning down at least 21 admission referrals in October

- Insufficient staffing, inability to meet specific needs, and difficulty of weekend admissions to staff to and process were the top three criteria given for admission decisions.

“Seniors and their caregivers are being left behind,” the LeadingAge Minnesota analysis found.

The same story is told in other states, such as Kansas, said Rachel Monger, vice president of government affairs for LeadingAge Kansas. A large health system in Kansas City recently complained about not being able to discharge patients to post-acute facilities, she told McKnight’s Long-Term Care News

“We had to explain to them that nursing facilities can no longer staff enough beds, even in major metropolitan areas, to meet demand,” she said. “If you are an older person in need of services right now, you are feeling the full effect of the staffing crunch.

“It is a frustrating and frightening situation we find ourselves in,” she added. “The next question is how long we think the government is willing to put an entire population of people at risk before they step up to the plate and properly fund long-term care.”

The Pennsylvania Health Care Association surveyed its workforce in 2021 and got responses similar to the Minnesota statistics. In March 2022 the PHCA dug deeper into the access-to-care issue analyzing information from December, 2021 to February, 2022.

“It was during that time we were hearing about hospitals reaching capacity because they were unable to discharge patients to nursing homes and COVID-19 cases were spiking with omicron,” PHCA director of external communications Eric Heisler told McKnight’s. “What we uncovered was that 60% of the respondents said they declined admission referrals during that three-month period. Of those facilities that declined admissions, each facility averaged about 20 referral declines a month. The survey gave us a better look at what waitlists look like to get into nursing homes with an average of eight people on a nursing home waitlist, and that residents were traveling further distances to receive care.”

Heisler said another key highlight from that survey was that nearly 50% of respondents revealed they had, on average, 32 licensed beds they were unable to use because they didn’t have enough workers to staff them. He said a federal nursing home staffing minimum mandate that many view as inevitable could be disastrous.

“When you think of Pennsylvania averaging 32 open beds, requiring more workers for one resident doesn’t necessarily help staff those open beds, especially when there currently isn’t a pool of caregivers to hire,” he said. “Pennsylvania developed staffing ratios that not only can help enhance care, but the ratios were attainable and somewhat funded. If a federal staffing mandate is unattainable and unfunded, you will continue to see many open beds and growing waitlists of seniors and adults with disabilities trying to access care.”