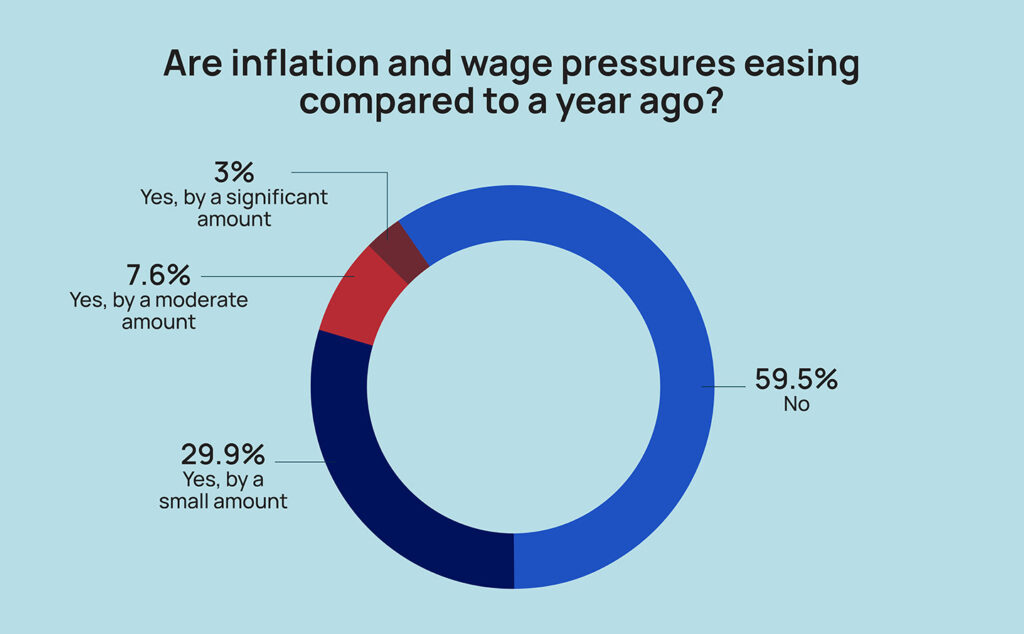

While the rate of inflation has cooled considerably this year, very few nursing home leaders are experiencing any relief, according to results of the 2023 McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey.

Just about 3% of respondents said they had seen inflation or wage pressures ease by “a significant amount” compared to a year ago. Another 8% reported “moderate” improvements, while nearly 30% reported they’d seen pressures ease “by a small amount.”

That left nearly 60% of administrators and nurse leaders who felt they’d seen no relief at all. That may be because prices aren’t falling, and in many cases are still going up, albeit more slowly in key categories.

The 2023 McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey drew more than 500 responses from directors of nursing, assistant directors of nursing, and administrators and their assistants.

“I think we’re generally in a better place than we were a year ago, but it’s not great,” said Lisa McCracken, director of senior living research and development at investment banking firm Ziegler. “The wage increases are not escalating at the same pace as what they had been. There were just those quick jumps, not even year over year, but sometimes month over month or quarter over quarter.

“We are hearing that there are some signs of some improvement on that front, but that’s not to say they haven’t been through a lot of blood, sweat and tears and pain.”

In an interview with McKnight’s Long-Term Care News, McCracken also noted that charges for food and fuel, two other major cost centers in skilled nursing, also remain elevated.

Her comments came just ahead of the latest inflation report Wednesday from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It showed that prices nationally jumped 3.7% in August compared with the year prior, and 0.6% compared with the previous month. Yet even a significant drop in a range of key categories from the 9% inflation rates seen last summer doesn’t necessarily offer relief to cash-strapped nursing homes.

Increased costs can make themselves felt for months or even years after inflation peaks, noted Steve LaForte, director of corporate affairs and general counsel at Cascadia Healthcare.

“We are seeing some easing of inflationary pressures, but given that rate-setting is behind our current operating expenses, we are still feeling the negative effects of increased costs,” he told McKnight’s this week.

He believes cost escalations that began during COVID are a good argument for tackling longstanding issues with the Medicaid and Medicare payment systems. While Medicaid’s state entitlement programs are funded partly by the federal government, that’s done “without real levers on rates” when prices soar.

“What we really need is a coherent system of reimbursement for means-tested long-term care, and the rates need to be set by the Feds similar to UPL [Upper Payment Level models used in some states] and have a market-based inflation adjustment,” he said. “To me something like that would be both economically logical and ensure sustainability.”

Costly choices continue

Some states in the last year have revisited their rate-setting practices, with many nursing homes lobbying for reform after facing tough choices with daily Medicaid pay often based on costs from two years ago.

But until true inflation relief comes, most providers continue making cost-cutting measures that may limit patient’s access to care and inhibit innovation.

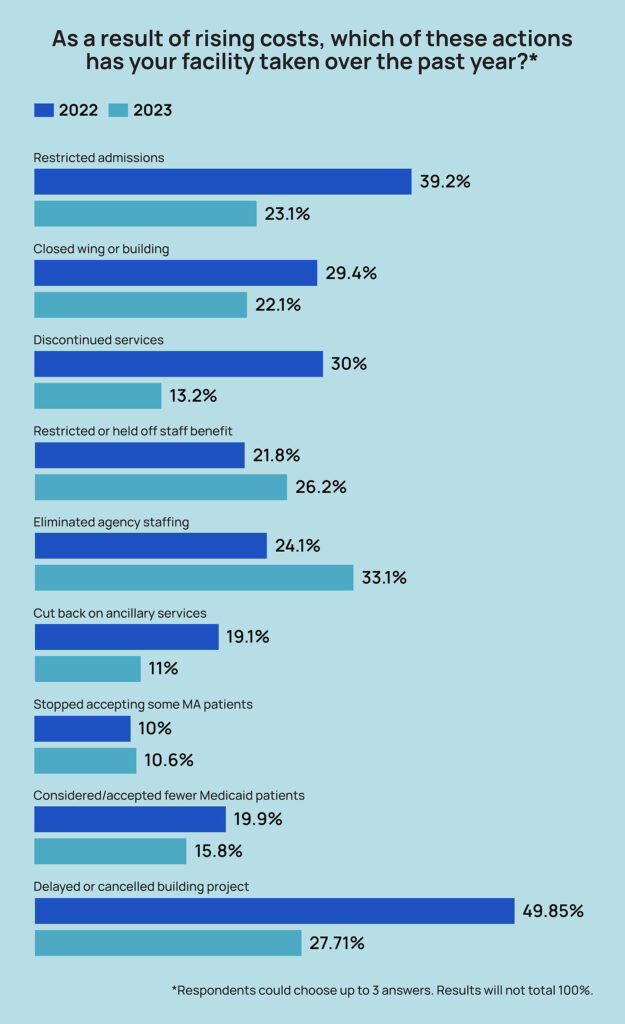

Nearly 28% of respondents in this year’s Mood of the Market survey said they had delayed or canceled building or capital projects to help offset rising costs over the last year. That’s down from a staggering 49.9% in 2022, showing that for some providers, it’s not possible to put off needed work anymore.

“In some areas, you’ve got to do it: Life safety issues and function are your priorities,” said Ted LeNeave, CEO and founder of Iowa-based Accura Healthcare. “But absolutely, 100%, we’ve delayed doing any major upgrades or facelifts. And that’s only possible with our relationships. Does the carpet need to be replaced in some areas? Yes, but the residents and families, they understand times are tough, and we’re transparent with them. They know it’s on delay.”

Accura also made some other strategic moves that made operational and financial sense in the current environment. Those included shifting some double occupancy rooms to private rooms and decreasing SNF bed licensure in some buildings to hold lower patient counts.

Providers in Iowa operating at under 85% capacity are paid a lower daily rate, so by lowering potential SNF occupancy, facilities are technically more full and take a higher rate.

That’s a trend that McCracken saw in collecting data for the forthcoming 2023 LZ200, which shows not-for-profit senior living communities reported fewer nursing beds this year compared to last year. An August Ziegler CFO Hotline survey also showed 48% of life plan communities had or planned to decrease nursing beds.

Agency diet

Accura and Cascadia both also trimmed agency staffing to help reduce costs, joining 33% of survey respondents whose organizations did the same. That was up 9 percentage points, from 24% in 2022.

“This was an initiative we set in motion at the start of the year, with a goal to eliminate and we have been materially successful,” LaForte said. “It combines our accent on culture, our engagement with current and recruited employees and incentivizing current employees to help with recruiting.”

While that agency was being driven out but before enough permanent staff was replaced, Cascadia also limited admissions. That method was favored by 23% of survey-takers this year, down from 39% in 2022.

The share closing a wing or unit also fell, from 29% last year to 22% this year.

Eliminating agency is also a good business move for those whose financial pressures are leading them to consider a merger or sale, McCracken said.

“It’s definitely on the radar of the investor community, certainly as well as potential affiliation or acquisition partners, just from an expense standpoint,” she said. “You’re seeing figures in the millions, millions, that organizations are spending on agency staffing. So I can understand why it’s a significant goal of an organization to be agency free. I have seen that come through a lot, and a number have done it through continued adjustment on the wage side.”

What comes next?

Of course, one financial pressure that didn’t come into play this year, but could soon, is a federal staffing mandate estimated to force some 75% of nursing homes to bring on more workers.

Exactly how providers will manage the additional costs — projected at $40.6 billion over 10 years by federal officials — is a looming concern for many.

“If you look at skilled nursing margins, it’s not like providers are making a ton of money in that space. There’s definitely going to be added pressure in that space,” McCracken said.

She said the proposed rule could be an impetus for more providers getting involved in value-based care arrangements, as they try to bring in more revenue to support an expanded workforce.

“Fee for service is going to go away and if you’re not at the table with being a real player in those value-based care arrangement, it’s going to be incredibly, incredibly difficult to bring any additional margin to even try to respond to things like the staffing mandate or other things that will come down the pike,” she added.

“Something is going to have to change. That whole staffing mandate is just one additional spoke of the wheel, and it’s a broken wheel. The system is badly broken at a time when we’re looking at just an age wave that is going to be demanding care and services.”

This is the final article in a four-part series on the 2023 McKnight’s Mood of the Market survey. The first on job satisfaction appeared Aug. 31, followed by the second on flexibility demands on Sept. 6 and the third on those driven to quit appeared Sept. 8.