Tying increases in state Medicaid rates to wages would be an important way to address the disproportionate representation of Black women in long-term care’s lowest paying positions, say researchers behind a new Health Affairs study.

In addition to increasing pay, providers and policymakers must also build better career ladders and address racism “in the pipeline” to reverse troubling historic trends, wrote Janette Dill, Ph.D., of the University of Minnesota, and Mignon Duffy of the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

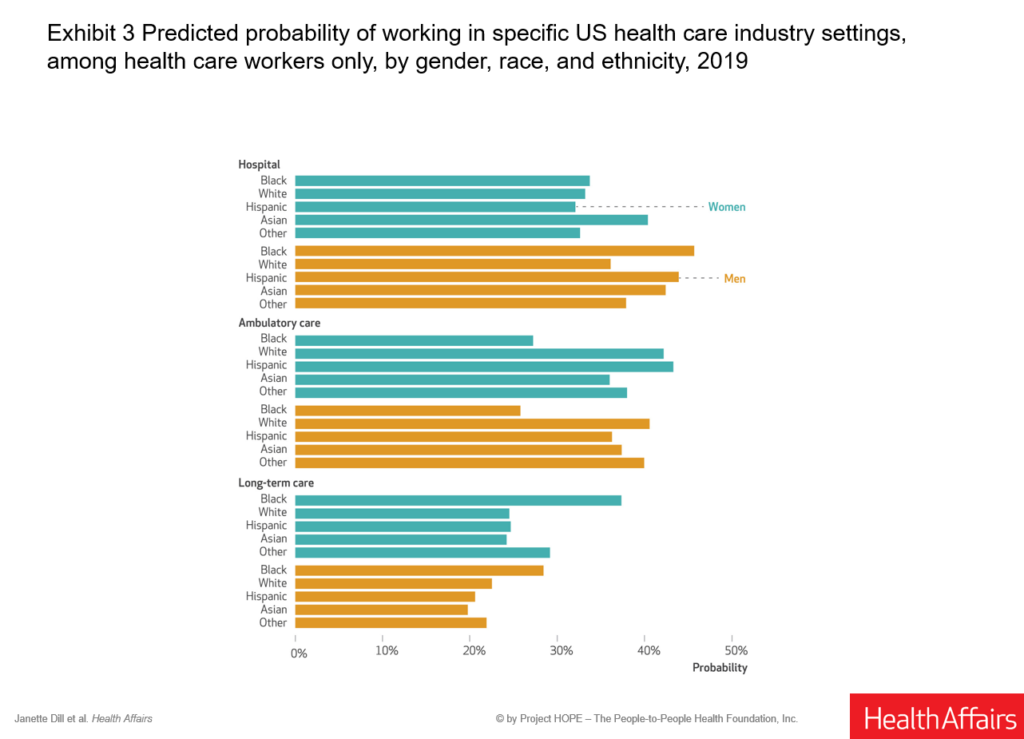

Reviewing census data from 2019, the pair found more than one in five Black women in the labor force were in the healthcare sector. But they are most likely to work as aides and LPNs, traditionally the least well-paid positions in healthcare. In long-term care, they make up 23% of the workforce, compared to 12.1% of the hospital labor pool.

Overall, 40% of Black women in healthcare are in long-term care settings, in jobs often characterized by low wages, lack of benefits and hazardous working conditions, study authors noted.

“Black women work overwhelmingly in the healthcare jobs that have been constructed as menial, or the ‘dirty work’ of care — direct care of older, disabled and ill bodies and bodily functions,” Dill and Duff reported. They traced a direct link to racial exclusion laws that persisted through the 1960s and to roots in slavery. “The legacy of that discrimination as well as the associated stereotypes are not easily undone.”

In an article published Monday, the authors recommended increasing the federal minimum wage in a way that includes workers in private facilities. They also called for improved state Medicaid funding to help address the economic impacts of racism.

“To ensure that wage increases do not further exacerbate staffing shortages, the rate at which facilities are reimbursed for patient care in these programs must also be adjusted accordingly and designated specifically to be passed through to workers,” they wrote.

They also recommended the establishment of more “meaningful” career leaders, including advancement based on completion of a middle-wage healthcare credential. Finally, they called for a focused effort to address persistent biases and stereotypes about what roles Black women should hold in healthcare.

“Investing in Black women through targeted investment in care infrastructure can begin to undermine some of the ideological constrictions and structural barriers that have devalued both,” they wrote.

Citing previous research, Dill and Duff noted Black women are more likely to work in nursing homes that are most understaffed and under-resourced, leading to greater risk and exposure to injury. They also found “more marginalized black women, including immigrants and those who do not identify as biracial (and may have darker skin) are more likely to be employed in the healthcare sector.”