Patients who recover from COVID-19 are likely to gain additional protection from a vaccine booster when compared to their peers who haven’t caught the virus, according to a new study.

The finding could help determine the ideal COVID-19 booster shot timing, researchers say.

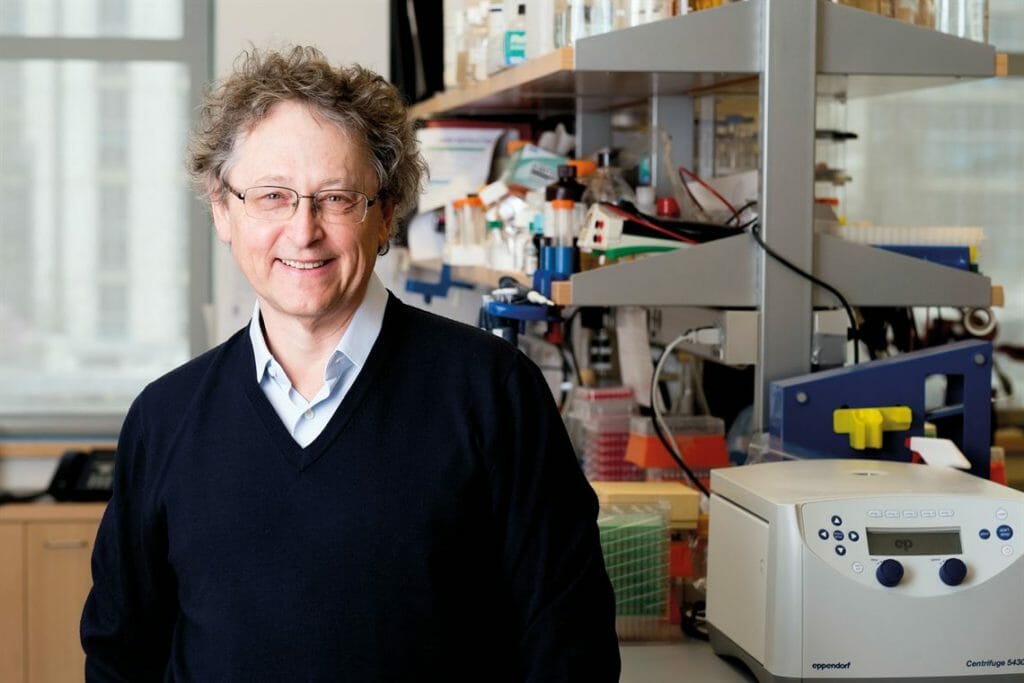

Investigators compared blood samples from convalescent COVID-19 patients to those from mRNA-vaccinated study participants who had never suffered natural SARS-CoV-2 infection. As expected, both groups had a buildup of short-term protective antibodies, as well as “memory antibodies” — made by memory B cells — that can last for years, said Michel Nussenzweig, M.D., Ph.D., a molecular immunologist at Rockefeller University, New York City, NY.

After two months, these memory antibodies tended to stop accumulating strength in the vaccinated participants — but not in the recovered COVID-19 patients, he and his colleagues discovered.

In patients who had experienced a SARS-CoV-2 infection, “memory B cells continued to evolve and improve up to one year after infection. More potent and more broadly neutralizing memory antibodies were coming out with every memory B cell update,” he reported.

This suggests that memory B cells produced by a natural infection may outperform those produced by the mRNA vaccines. And convalescent individuals may therefore have a greater response to a booster vaccination as well, Nussenzweig and colleagues said. This further protection could be taken into account when deciding when booster shots will be most effective and for whom, they added.

“If the goal is to prevent infection, then boosting will need to be done after 6 to 18 months depending on the immune status of the individual. If the goal is to prevent serious disease, boosting may not be necessary for years,” Nussenzweig said.

The findings do not suggest that vaccination isn’t necessary, he and his colleagues cautioned. The benefits of stronger memory B cells do not outweigh the risk of disability and death from COVID-19, they said.

“While a natural infection may induce maturation of antibodies with broader activity than a vaccine does — a natural infection can also kill you,” Nussenzweig said. “A vaccine won’t do that and, in fact, protects against the risk of serious illness or death from infection.”

Is prior infection protective?

Despite growing evidence that prior infection is highly protective against future COVID-19 illness, the extent to which it works remains under discussion in the scientific community.

“Like many disputes during the COVID pandemic, the uncertain value of a prior infection has prompted legal challenges, marketing offers and political grandstanding, even as scientists quietly work in the background to sort out the facts,” wrote Arthur Allen in a recent report by Kaiser Health News.

Some scientists also believe that the role antibodies play in providing protection is still uncertain as well.

“We don’t yet have full understanding of what the presence of antibodies tells us about immunity,” Kelly Wroblewski, director of infectious diseases at the Association of Public Health Laboratories told KHN.

The current study was published in the journal Nature.