A new report predicts post-acute care providers will miss out on nearly $20 billion in revenue this year, not due to COVID but rather staffing challenges.

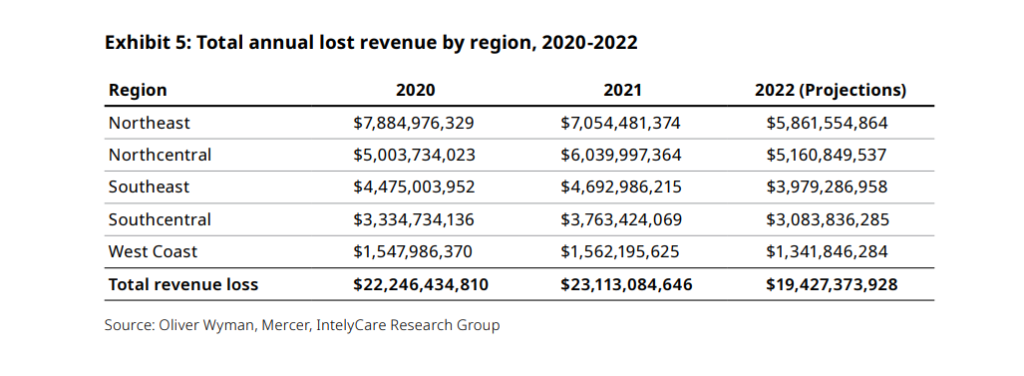

Consulting firm Oliver Wyman calculated that understaffing resulting in lower occupancy will lead to $19.4 billion in unrealized revenue. The biggest hits will come in the Northeast and North Central U.S., the firm projected. The study also sought to measure just how much various staffing needs and strategies are costing providers.

“It has become extremely difficult since the pandemic to maintain the workforce needed to reach full census,” Deidre Baggot, a partner at Oliver Wyman, said in announcing the study results Thursday morning. “As a result, facilities lost between $2,656 and $7,771 a day in 2020 and 2021 and are estimated to lose between $2,330 to $5,882 this year. To increase admissions, it’s imperative that post-acute care facilities rethink how they manage their workforce and start to spend more strategically on staffing.”

Oliver Wyman also found the average nurse hours worked increased by up to 15% across the workforce due to understaffing. The typical nursing assistant now works nearly 52 hours per week, and 60% of those who left their jobs cited insufficient staffing as a reason.

The study used data from hundreds of providers across the country that was compiled by asset management and HR consulting firm Mercer. The analysis was commissioned by post-acute care staffing firm IntelyCare.

The findings follow long months in which providers have grappled with hiring challenges despite offering significantly higher wages and called for action on aggressive agency staffing tactics. They also have pursued alternative approaches such as flexible scheduling and internal pools to attract potential workers.

There’s an upside and a downside to working with agency staff, but they appear here to stay for the foreseeable future, said Rick Abrams, CEO of the Wisconsin Health Care Association/Wisconsin Center for Assisted Living.

“The relationship with many of our members and their staffing agencies has not been a positive one. There were agencies that took advantage of the environment during COVID. It’s moderated a little bit, but it’s still a concern,” he told McKnight’s Wednesday. “But when we’re talking about lost revenues, the access piece is really, really important. The last thing we want is any more facilities to close.”

A semi-permanent solution emerges

In Wisconsin, 50 skilled facilities have closed since 2016, and many of the roughly 360 remaining have reduced their number of licensed beds as staffing problems have grown. Abrams’ members are reporting about a 30% vacancy in certified nurse aide positions leading to occupancy in the high 60% to low 70% range.

He also added that some agencies have charged 200% or more of the going rate for CNAs and nurses.

An analysis of Mercer data finds, however, that hiring contingent workers may be an efficient way for nursing homes to keep their doors fully open without hiring full-time, permanent employees in a tight and expensive labor market.

IntelyCare has estimated that about 7% to 27% of staffing will always need to be “flexible” to cover vacations, sick days and other absences or shortages. The company suggests its clients build an internal float pool of about 20% to limit agency, or contingent, staffing to about 7%. For many providers, however, that number might seem low considering a shortage of nearly 300,000 CNAs is expected to persist through 2030.

Matt McGinty, IntelyCare’s chief revenue officer, agreed that the quality of the staffing agency partner matters for providers doing their best to remain open to serve as many patients as possible. He addressed the issue in a recent McKnight’s webinar.

“The key is the partner you choose. Do they offer education? Do they have professional development? Do they have clinical development? Do they hire their employees as W2 and are vested in them or are they 1099 contractors left to fend for themselves?” he said.

“Plan for the use of flexible staff ahead of time, proactively dedicating a set portion of your workforce to per diem so that you can better predict and control usage and spend. If you’re always reacting to cyclical events like holidays and the start of the school year at the last minute, you’re only making it more expensive to fill these shifts.”

Emotional reactions to tough numbers

Some providers have limited occupancy or temporarily stopped accepting patients when staffing shortages become too dire, or if the cost of hiring makes operating costs unsustainable.

“Because it’s been so difficult to find nurses, we’ve had to hire agency staff at three times the cost to maintain the level of quality care our residents deserve. We are now paying physician wages for frontline caregivers and nursing staff,” said Nate Schema, president and CEO of Good Samaritan Society. The organization’s rural nursing homes often have more than half their beds filled by Medicaid patients, and it has recently closed several facilities, citing staffing difficulties in Nebraska and North Dakota.

“Unfortunately, these staffing challenges have led to a situation that is not sustainable, forcing us to make difficult decisions about how and where we can provide care and services,” Schema told McKnight’s Wednesday.

But IntelyCare co-founder and CEO David Coppins said closing doors instead of paying more for labor — especially when the costs are well managed and planned for — could contribute to permanent access issues for patients in need of skilled nursing.

“The sources that feed that (occupancy) normally will find alternatives. They’re already creating their own,” he said, noting acute-care providers’ increased use of home health and in-hospital wings to hold would-be SNF patients when there are no local beds available.

He recounted the tales of two large providers who spoke at last week’s LTC100 conference. One CEO kept census intentionally low as a means to drive out agency staff but was operating at a 5% loss. Another CEO embraced agency staff as a needed part of the workforce and had higher census than prior to the pandemic, and was operating in a positive margin.

“The biggest issue we’re seeing is because of the pressures that facilities are under right now, from the federal government, from CMS, and the cost of staff and necessary pay rates they have to give to get them on staff … it can turn into an emotional reaction,” Coppins added. “You need to look at the economics rationally.”

Is contingent staff to blame?

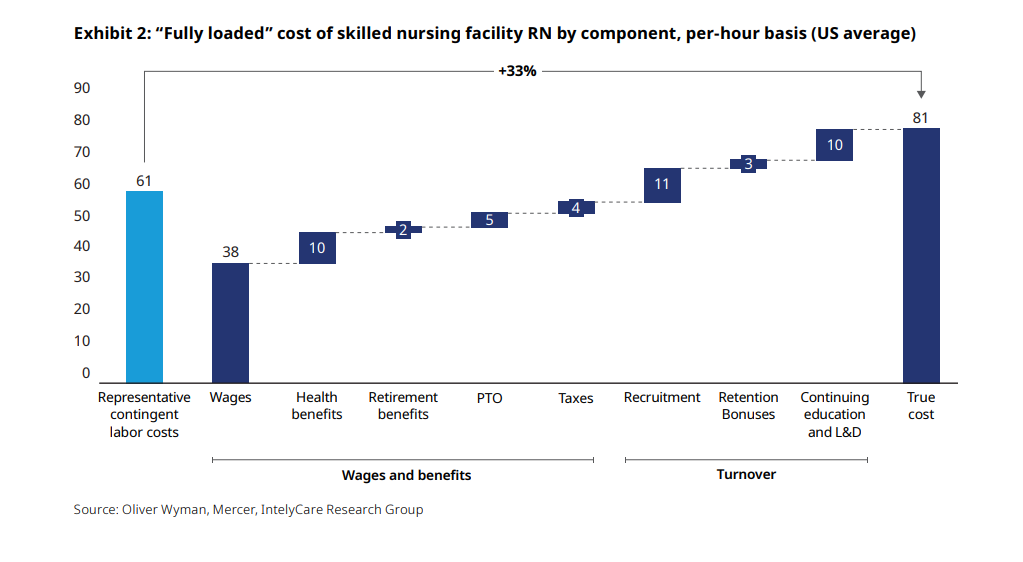

The Oliver Wyman analysis aims to compare “fully loaded costs” to help operators understand how and what they’re spending, not just on wages but on recruitment, retention and other human resources efforts, too.

The study found that on an hourly basis, a full-time employee costs a facility 1.9 to 2.2 times their hourly wage rate when accounting for benefits and recruitment expenses. Staffing firms, however, absorb the cost of recruitment, as well performing payroll and tax duties.

When those ancillary costs are accounted for, the cost of filling a shift with a full-time registered nurse is 33% higher than the contingent labor rate that is being paid. For nursing assistants, the cost is 26% higher than contingent.

“There’s this feeling that the contingent staff is sort of to blame for all of their [nursing homes’] financial woes,” Coppins said. “In reality, it’s either going to cost you $3 to $4 more per hour or it’s going to cost you $3 to $4 less per hour to use contingency. It’s not the same as travel nursing during the height of COVID. We’re talking about per-diem, day-to-day costs.”

Oliver Wyman also has developed a calculator that operators can use to test their own staffing numbers and determine how various levels of agency use might shift spending.

As Abrams noted, pricing is just one factor to consider. Providers also need workers who will show up consistently, and agencies that won’t pirate permanent staff. Providers also need relationships that feed community stability.

“The facility staff should embrace these agency staff as part of the team,” he said. “They’re filling a need in the facility, but they’re just helicoptering in [temporarily]. The continuity of care, it’s so important in custodial care.”