Are horse people “solid people,” or are they “crazy people”?

After three straight days of 5 a.m. rise-and-shines to get my daughter Emmy ready for showing, I initially said, “Girl, these people are nuts!”

However, after watching a group of tiny 7-year-olds wake before the sun with smiles, joyfully clean stalls, bathe their ponies, and ride with pride, I was changing my tune to, “Girl, your horse friends are solid people.”

Emmy and her group of barn friends are truly a special pack.

Their love for riding is 98% work to prepare for the actual event of riding.

I am intrigued by their chats about hard work and understanding of why their coach pushes them: “Kalena is hard on us because she wants us to learn and do better.”

Their constant support for each other: “We don’t care who wins. We just want ribbons for our barn!”

And the innate sense that no one leaves until all of the work is done: “What can I do to help? Bathe, shovel, graze your horse, anything at all?” (Which I have also learned may just be an excuse to never, ever leave.)

What if we all, as post-acute care providers in SNF, HH, IRF and LTCH approached care this way? Imagine the difference for our patients if we all understood no one’s work is done until we are all done.

This tiny pack of girls has mastered the art of what it truly means to support one another through the good times (ribbons!) and bad (ponies can be naughty and will escape their cross rails!). But onward to post-acute care and what we see coming in the future.

Last week we as an industry saw RTI International release a report titled: CMS Report to Congress: Unified Payment for Medicare-Covered Post-Acute Care Analysis and Development of the Prototype Unified PAC Prospective Payment System Called for in the IMPACT Act.

This report outlines findings specific to present the prototype for the Unified PAC (UPAC) PPS.

Is UPAC a new term to you?

Let’s start with some background here.

Post-acute care (PAC) represents an important component of the healthcare delivery system in the United States, with the Medicare fee-for-service program spending more than $57 billion on these services in 2019 (The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), 2021a).

PAC providers include skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), long-term care hospitals (LTCHs), and home health agencies (HHA) [§ 1899B(a)(2)(A) of the Social Security Act].

UPAC is associated with aims from IMPACT.

In 2014, the Improving Medicare Post-Acute Care Transformation (IMPACT) Act was signed into law. A key provision of the IMPACT Act was the development of a technical prototype Unified PAC prospective payment system (PPS) that would set payment for PAC services on the basis of beneficiary clinical characteristics rather than type of provider.

The IMPACT Act also required the use of standardized data elements collected across the different PAC settings to be incorporated into and determine payments under the prototype.

The full RTI report — please read it! — presents the prototype for the Unified PAC PPS and the analyses used to design and calibrate it.

They begin by describing the data used in this analysis, including Medicare claims and enrollment data, PAC assessment data, and Medicare cost report data.

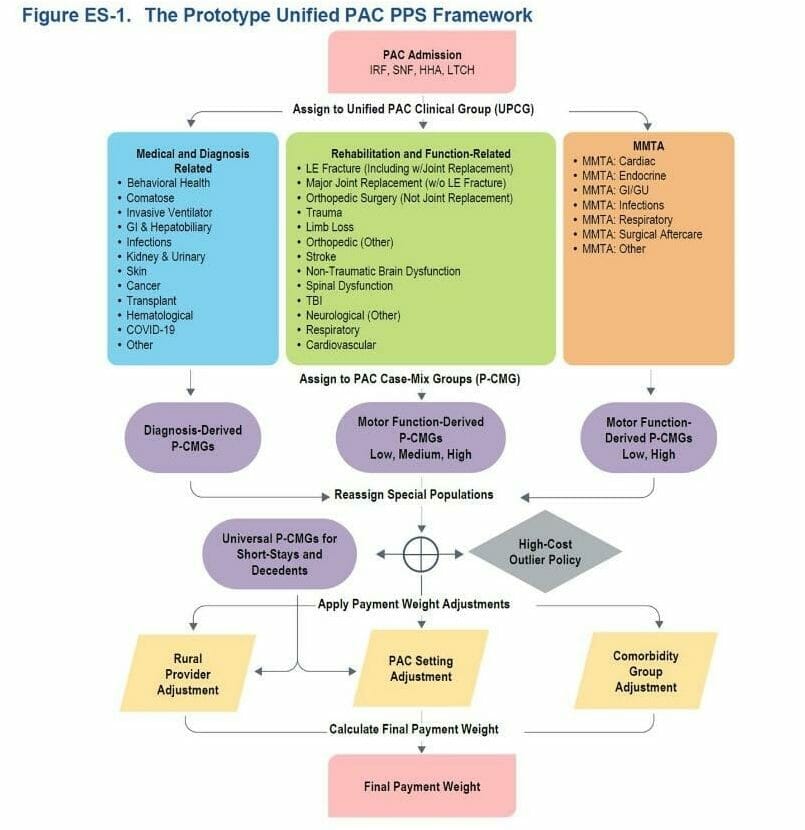

The prototype Unified PAC PPS framework is presented in Figure ES-1 and described throughout this column. It bases payment on several key factors relevant to beneficiary needs and costs of care. These include:

Framework Definitions:

Unified PAC Clinical Groups (UPCG): 32 distinct clinical condition groups representing the patient’s primary reason for PAC. These UPCGs are associated with different types of beneficiary needs, both clinically and in terms of costs of care. They can be conceptualized in three general categories:

- Rehabilitation and Therapy-Focused (Rehabilitation)

- Medical and Diagnosis-Focused (Medical)

- Medication Management, Teaching, and Assessment (MMTA)

PAC Case-Mix Groups (P-CMG): Subgroups within each UPCG differentiating patients’ needs on the basis of clinical characteristics and relative costliness. Characteristics used include the following:

- Self-care and mobility (motor) function (as reported using standardized data elements on the PAC assessment instrument); higher scores indicate higher functional abilities

- Primary PAC diagnosis

- Diagnoses and procedures reported during a prior acute stay

Comorbidity Groups: A measure of clinical complexity and relative costliness based on the combination of secondary diagnoses reported on the PAC claim and information reported on the PAC assessment instrument. A higher index score indicates higher costliness.

PAC Setting Types: An indicator reflecting the type of PAC setting in which the beneficiary was treated.

Rural Settings: An indicator that the provider is operating in a rural area.

The report continues by outlining research, findings, setting specific considerations, definitions for quality and so forth. Again: Please read the full report!

Another unique element was around the concept of care coordination and the role of patient navigators.

As stated, and as we all know, navigating the entire UPAC is challenging.

The care trajectory for an individual beneficiary can be complicated. Many beneficiaries receive PAC services from more than one provider in their care trajectory. For example, of beneficiaries discharged to a SNF after an acute hospitalization in 2017, 63.1% go on to use another acute or PAC service within 90 days, and of beneficiaries discharged to an IRF, 79.1% used another acute or PAC service within 90 days (data not shown).

Transitions of care can present significant challenges for both beneficiaries and providers, as they involve the transfer of information between patients, caregivers and providers, which can be complex (Figure 4-1)

An idea that was discussed at panel meetings during the prototype development is the potential role for a patient navigator.

Goals for such a role could include providing additional patient and family education regarding transitions of care and ensuring the transfer of relevant information across providers.

This role would primarily focus on handoffs at admission and discharge. Facilitating smoother transitions and improving patient and family education at discharge would support a beneficiary-centered approach to care, help ensure health equity, and could be valuable for beneficiaries and for the Medicare program.

The conclusion from RTI… well, it’s challenging!

Unifying Medicare’s payment systems across the four key types of PAC providers while still capturing important differences in the types of patients they care for, and the regulatory environment in which they operate is challenging.

The proposed framework applies a uniform approach to case-mix adjustment across all beneficiaries receiving PAC for different types of PAC providers while accounting for factors independent of patient need that are important drivers of cost across PAC settings.

What can providers do in the immediate time ahead?

First, read the full report. Then consider, who is your PAC? Do you have effective systems now for communicating with care settings outside of your individual (assuming most readers here are SNF) alone? Could you consider the use of care coordinators? Are you communicating post-discharge with patients, their loved ones or families? Can communication facilitate your knowledge on how you can improve your discharge planning procedures?

Really, now is the time to find your PAC, and learn how to work together more effectively.

Starting first thing in the morning, up before the sun, motivated by hard work, not being afraid of getting dirty, knowing the effort is worth the reward for those we serve, and always being willing to say, “how can I help?”

Take some notes from horse people. They are some solid humans, even starting with their tiniest of packs.

Renee Kinder, MS, CCC-SLP, RAC-CT, is Executive Vice President of Clinical Services for Broad River Rehab and a 2019 APEX Award of Excellence winner in the Writing–Regular Departments & Columns category. Additionally, she serves as Gerontology Professional Development Manager for the American Speech Language Hearing Association’s (ASHA) gerontology special interest group, is a member of the University of Kentucky College of Medicine community faculty and is an advisor to the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology CPT® Editorial Panel. She can be reached at [email protected].

The opinions expressed in McKnight’s Long-Term Care News guest submissions are the author’s and are not necessarily those of McKnight’s Long-Term Care News or its editors.