The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services notice of proposed rulemaking and the report on which it is based have made the foundational point that more staff in nursing homes will result in better patient care and outcomes. While this relationship may seem self-evident, the actual data to support this axiom is pretty thin. But to dismantle the proverbial deck chair while the entire vessel is sinking will quickly lose everyone’s attention.

The issues with these proposed staffing mandates are multiple. First, the available supply at-large of both registered nurses (RNs) and nursing assistants (NAs) is inadequate to meet the proposed requirements. It is a key fact that the supply of RNs and NAs is inelastic; they cannot be manufactured overnight. There are not plenty of RNs and NAs on the sidelines and there’s no indication that, as soon as they see possible opportunity, the ones who left will come back to nursing home jobs.

There wasn’t enough supply before the pandemic, there are even fewer now, and it’s wishful thinking to build a plan on the fiction that they’re eager to return – especially for the same pay rate. Second, these unfunded mandates will drive many more nursing homes out of business. Nursing home providers will be punished or rewarded based on location, payment mix and other factors, which are irrelevant to nursing home quality.

If we’re looking for ways to improve nursing home quality, the proposed CMS staffing mandate isn’t it. Everyone who operates a nursing home agrees that more staff will help. Lacking any promise of funding for the mandated staff means that operators must find funding. Among those operators that will remain afloat, the consequences mean delaying/denying investment into capital needs, information technology, patient monitoring and optional assistive care devices, health equity programs and improving resident quality of life. This proposed rule, lacking any support for the $40 billion, 10-year estimated cost, will do harm as a result of good intentions.

Supply

Here is the picture of the current RN and NA supply from the payroll based journal (PBJ) from nursing homes:

This presents a clear picture of nursing home workforce in the RN and NA categories for recent periods. There has been a slight decline in RN hours and a slight increase in NA hours. The actual average RN hours per resident day is now higher than what CMS has proposed (0.58 v. 0.55) and NA hours are lower than the standards proposed (2.16 v. 2.45).

Where’s Waldo?

Looking at the most recent CMS reported PBJ hours from September 2023, the reported RN supply is 14.4 million hours more than the minimum required.

| Count of SNFs | Estimated Annual Pt Days | Total annualized RN (PBJ) Reported Hours | Total annualized hours needed for RN Mandate | RN hours over / (under) the mandate |

| 14,993 | 439,497,485 | 256,163,054 | 241,723,617 | 14,439,437 |

Yet, over half (50.2%) of SNFs will need to hire more RNs. This shows a geographic distribution problem with the existing RN supply. If you are an operator that happens to be located in a marketplace with an oversupply or RNs, congratulations! Otherwise, you’re out of luck. This isn’t addressing the quality challenges facing nursing homes in an equitable or feasible manner.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) there are 124,690 RNs employed in SNFs. Assuming that each SNF provider employs an RN as a director of nursing services, this person is probably not providing direct patient care. Some RNs also work in nursing homes in other administrative roles, but for the sake of simplicity, we have not tried to adjust for other non-clinical staff. The adjusted RN workforce is approximately 109,697. Moreover, to calculate the over/(under) supply, we have to account for turnover. Making these adjustments, we estimate that there is a hypothetical shortfall of ~ 25,000 RNs based on the proposed CMS staffing requirements.

The situation with NAs, however, is far different.

According to BLS, there are 447,940 NAs employed in SNFs. To be in compliance with the proposed staffing standard of 2.45 hours per resident day, the average SNF would have to employ 36 NAs. The national shortfall of nursing assistants needed to meet the proposed CMS standards is at least 86,000 and may be as high as 130,000.

Additional staff = additional, unfunded costs

How much would this additional staff cost? The CMS notice states the costs as:

$32 million in year 1; $246 million in year 2; $4 billion in year 3; with costs increasing to $5.7 billion by year 10. We estimate the total cost over 10 years will be $40.6 billion

The year-1 costs work out to $2,134 per SNF. Without putting too fine a point on it, this is less than one month’s recruitment costs for most nursing homes.

Recruiting & retaining

And this brings us to recruitment. The difficulty recruiting and retaining direct care workforce has been in the forefront of the sector since before the pandemic. Few other subjects have received more attention. To suggest that greedy operators haven’t hired more staff in order to fatten their bottom lines ignores the facts that: 1. There aren’t staff willing to work in SNFs at the pay rates which Medicaid payments make possible; 2. SNFs have very frail bottom lines, and 3. Temp agency use has skyrocketed and remains high, eating through what’s left of the bottom lines.

What are the recruitment and retention plans incorporated in the proposed rule? The only one is a circular-logic suggestion that more staff will lead to greater retention. What’s lacking is a clear path to get there.

Results on provider supply

Workforce is one component of the overall long term care delivery system. Nursing homes in particular have been closing and going out of business due to unsustainable costs and declining demand. Implementing the proposed CMS staffing standards will certainly drive more nursing homes out of business. We estimate that 750- 1200 SNFs will need to close as a direct result of these unfunded staffing mandates; the carnage could be even worse. Putting these projections into perspective, the U.S. will have lost over 10% of its nursing homes since 2018.

Some say openly that this is a good outcome. However, most balanced sources recognize that available nursing home beds in the community are critical resources allowing hospitals to discharge patients and families to relieve their unsupportable care burdens.

Additional observations & caveats

Turnover – for the estimates above, turnover has been assumed to be very low. If and wherever RN turnover is higher than 23%, and/or if NA turnover is higher than 40% the shortfalls are worse. CMS reports that nursing homes have an average RN turnover of 50.4%. The proposed mandate relies heavily on provider planning — and luck — to reduce this number.

Pay rate competition – What pay rate would nursing homes need to offer in order to attract the RNs and NAs who are on the sidelines or who took jobs in other places? What would have to be offered ($$) to cause anyone to work in a SNF? Let’s consider NAs, and we can use a recent, fairly successful experiment by Newark, NJ, to attract teachers. The city offered entry salaries of $63,500 per year (~$31.75 / hour). To create a comparable incentive, the average rate of pay for a nursing assistant would have to be more than doubled – from $14.13 / hour to $28.26. In California, with the highest minimum wage, this would mean an hourly rate of $34.83 and for Georgia, the state with the lowest, an hourly rate of $16.29.

Is this “wishful thinking”? No more so than publishing a notice of proposed rulemaking without realistic consideration for the needed funding increases to attract the workers the rule requires.

Retirement –The age of the RN workforce is increasing, and fewer young nurses are being attracted to the field. Of particular concern is that ~40% of the overall RN workforce is over 50 years of age.

Burnout – A recent Health Affairs article looked at the decline of the RN workforce and concluded:

“Although it is difficult to disentangle the contributing factors, these likely include early retirements, pandemic burnout and frustration, interrupted work patterns from family needs such as childcare and elder care, COVID-19 infection and related staffing shortages, and other disruptions throughout health care delivery organizations.”

Poaching – Many RNs and NAs are being attracted away from LTC to hospitals or other clinic practices through higher pay rates, better conditions, flexible work schedules and recruitment bonuses. This market fact puts further pressure on the LTC sector and nursing homes in particular.

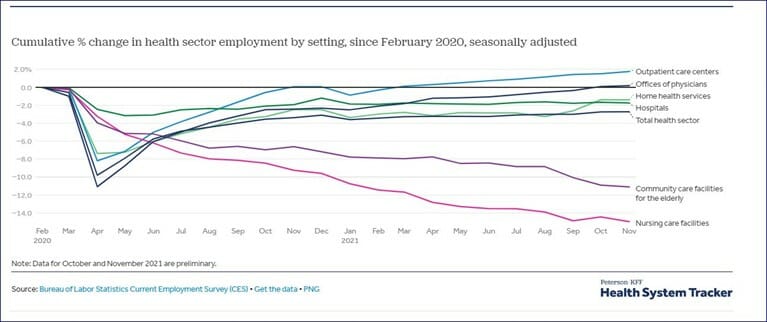

Workforce elasticity – The nursing workforce has suffered tremendous shocks since the pandemic and has not yet recovered. This tumult in the available workforce supply does not augur well for an unfunded mandate requiring providers to hire RNs and NAs who simply may be unwilling.

There aren’t enough RNs and NAs now, and the supply of NAs in particular is far short of the proposed requirements. NAs are also grossly underpaid; 46% live below the Federal Poverty Level. There really is no plan as to where the additional, needed RNs and NAs will come from.

If the workforce was on the sidelines due to pay, what must be paid to draw them back? If pay rate was not the factor that drove them away from LTC, what was it, and what can be done to mitigate those issues to attract them back?

Driving more SNFs out of business won’t punish the greedy or the profiteers – it’ll close the non-profit and rural operators serving Medicaid beneficiaries (mostly).

It stretches credulity to create a policy that cannot work today or tomorrow, based on your own data. As the adage goes, “If wishes were horses, beggars would ride.” The proposed CMS minimum staffing standards are too much wishful thinking and not enough planning.

Irving Stackpole is President of Stackpole & Associates and can be reached at [email protected].

John Sheridan is Vice President of CommuniCare and his contribution are his opinions alone and do not represent opinions of any other person or entity. He can be reached at [email protected].

The opinions expressed in McKnight’s Long-Term Care News guest submissions are the author’s and are not necessarily those of McKnight’s Long-Term Care News or its editors.

Have a column idea? See our submission guidelines here.