Long-term care workers are inundated daily with reasons to be emotionally and physically stressed. As a result, they are often cited as being some of the most unhappy employees in any industry. One key to changing this is to help managers, as well as employees, obtain the tools needed to create a positive workplace. Administrators and managers want to increase staff morale, lower staff turnover, and have an overall healthier work environment but often feel at a loss for knowing what can be done.

Additionally, the demand for long-term care is increasing, as is the need for workers—millions more elderly individuals are projected to be in nursing facilities, assisted living and home care services by 2050. So the stress experienced by managers and staff will increase, unless preventative steps are taken.

According to a study by the American Health Care Association, annual turnover rates among direct-care workers (nursing assistants and aides) are approximately 70 percent. In other words, two out of three nursing home or long-term care workers leave their jobs in the course of a year. The point? Getting a handle on reducing staff turnover is going to be critical for any long-term care facility to even begin to improve staff morale.

In a series of NHPCO studies, peer support, strong teams, and high staff morale have been shown to be important factors for team members to cope with the stress they experience. Another is for healthcare teams to learn to communicate appreciation to one another in ways that are meaningful. Having good relationships with team members play a significant role in the degree of job satisfaction for long-term care professionals.

The stress in long-term care is complex. Studies have found that it is on the rise due to the increased use of technology (e.g. electronic medical records), the multitude of rules and regulations, and the changes in the insurance industry. Obviously, the quality of workplace communication and relationships are greatly affected by this turbulent environment.

My professional expertise is in helping workplace environments become more positive and healthy, so I am fully aware of the negative, damaging communication that occurs in many work settings. In fact, sometimes I am appalled at the stories I hear from employees, supervisors and managers (the dysfunction impacts all levels of an organization) and the damaging statements and actions that occur in work-based relationships.

But I firmly believe we are not passive victims that don’t have the capability to impact those with whom we work on a daily basis. If you work in a workplace that is poisonous, damaging, and even potentially dangerous to the mental and emotional health of those who work there – there are steps you can take to make your workplace less toxic. You are not just a helpless bystander.

First, do a self-assessment. As I remind those groups to whom I speak, being “dysfunctional” is not limited to everyone else – we often contribute to the sickness of the system in which we work. (Surprise! You are not perfect and you are not right all of the time!) Ask yourself and consider, “What am I doing that really isn’t that helpful in creating a positive workplace?”

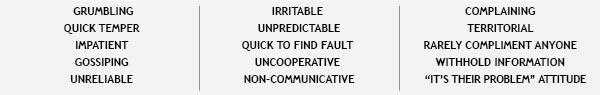

This could include both actions (complaining about a co-worker to another colleague) and attitudes (harboring anger and grudges for past offenses). Consider the following terms, and see if any might apply to you:

The second pro-active step you can take is to actively disengage from participating in negative interactions. This can mean – quit complaining, (remember the saying, “If you can’t say anything positive, don’t say anything at all”?)

When you are involved in a group discussion with other care providers and the conversation turns negative, excuse yourself. You don’t have to say anything, or sound like you are judging. Just quietly excuse yourself and don’t contribute. Your leaving will send a message – and may lead to a follow-up discussion with one of the your colleagues (“I noticed you left when we started griping about management’s lack of communication.” “Yes, I’ve decided to try to not engage in that type of discussion. I’ve found it really isn’t helpful.”) Note that this does not mean that staff should keep quiet about basic workplace needs going unmet, such as not having enough staff or managers available, unreliable equipment or insufficient breaks. These valid concerns can be addressed in more appropriate ways.

Beginning to communicate positive messages to others is the third simple step we each can take. A survey by the Boston Consulting Group found the No. 1 factor for employee happiness on the job is to receive appreciation, and for long-term care staff, this has been shown to be true. Often, the easiest way is to verbally share your appreciation for your teammates, and the work they do. A simple “thanks” can be meaningful – especially if it’s specific (“Jen, thanks for taking on that extra patient. That really helped me focus on the difficult situation I was dealing with.”) This can be effective in “softening up” even those colleagues who seem fairly hardened and angry, though it may take some time.

“That’s it?” you may ask. Quit being so negative and try to be more positive?

Yes, that is the starting point. We know that stressful health care environments are comprised of many components, but one of the key aspects is the accumulated negative communication (and lack of positive messages) feed off of each other and become like a poisonous gas which suffocates those working in it.

Also, we know that when individuals start taking responsibility for themselves and their actions, they begin to have a sense that they can make a difference. Then change starts to happen. Positive change is desperately needed in this field, for the sake of patients and staff, now and for the future of long-term care.

Paul White, Ph.D., is co-author of “The 5 Languages of Appreciation in the Workplace” and the “Motivating by Appreciation Inventory. For more information, go to www.appreciationatwork.com.