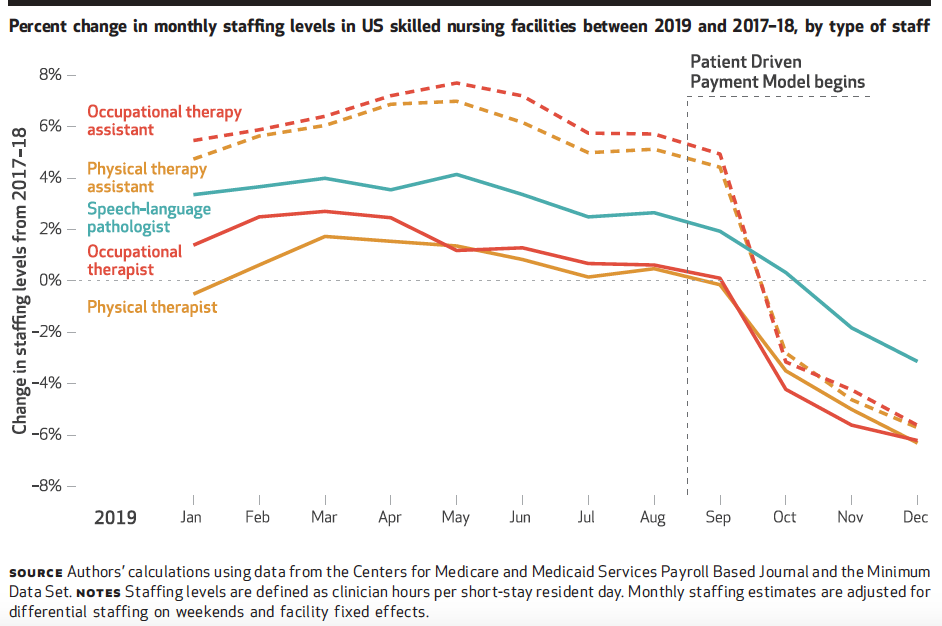

The first academic study of its kind has found that the first three months of nursing homes’ overhauled Medicare payment system at the end of 2019 led to a distinct drop-off in the employed number of licensed therapists and therapy aides.

But with retrenchment of about 5% for therapists and 10% for aides, the levels did not reach the drastic wipeout that some stakeholders had warned or complained about.

More revealing, however, should be results of an upcoming study on the level of therapy minutes delivered in the Patient Driven Payment Model era, the researchers noted.

Investigators used federal Payroll-Based Journal staffing data to compare therapy and nurse staffing hours before and after the Oct. 1, 2019, PDPM start date. Findings were released in the journal Health Affairs on Monday.

Staffing reductions were most pronounced among contracted therapy employees, the ranks of which had been slowly built up in advance of PDPM’s start, noted lead study author Brian McGarry, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at the University of Rochester.

“The initial results were less than what we expected, just based on the anecdotal reports, but we also have this sense there’s an unevenness to it,” McGarry told McKnight’s. “It was really facilities that had contracted therapy staffs were probably able to shift really quickly overnight and enact changes to their staffing levels. Those employed at nursing homes might be more of a lag, and it’s to be determined whether they actually do shed some staff to change the overall staffing levels.”

Overall effects of staffing cutbacks were “modest,” McGarry added, noting that the interruption in operating conditions caused by the pandemic made it impossible to determine whether they were one-time cuts or the start of a bigger trend.

“It’s definitely something that warrants continued vigilance,” he said.

Care outcomes concern

He added that a preliminary look at another database has shown “sizeable” reduction in therapy minutes, which could be an even bigger indicator whether outcomes may suffer. That study, however, is still in the formative stages and is not finalized.

Researchers and regulators are ultimately interested in whether staffing and therapy minutes changes will hurt quality of care. Conclusions for some of that could be a year away due to the availability of hospital discharge and readmissions claims data lagging other indicators.

“My gut is that nursing homes previously had a really strong and somewhat perverse incentives to deliver very high levels of therapy, probably beyond what was clinically indicated,” McGarry said. “I think this [staffing] change is probably reasonable, but what we’re really concerned about here is unintended consequences.”

Those could include reductions in therapy spending not evened out by additional spending on direct-care nursing. The researchers said they did not find evidence of therapy cutbacks accompanied by corresponding increases to nursing care.

The three-month sample window, however, may not have been enough to give a true indication, noted researcher Elizabeth White, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health.

“It will take a longer lense to see if case-mix changes over time,” and whether more nursing hours accompany it, she told McKnight’s.

“This is a story that will evolve,” she added. “There are going to be major changes in the nursing home sector in the next two to three years, so it will remain to be seen how everything plays out.”

Cliff-hanger remains

She said that study results did not necessarily reveal therapy villains or saints. Providers, she said, must pursue revenue paths that will help make up the difference between Medicaid rates and actual costs of care, a gap that has increased in recent years.

When the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services “provides them with an opportunity to increase their Medicare revenue, it’s expected you would pursue that in order to fund your business, and fund the care of the patients you care for, the long-term care patients whom you care for that you can’t make money on, but they still have a significant level of care that they need. So I don’t think there are good guys and bad guys.”

“I think it’s just unfortunately how the industry is funded. When there are payment incentives, people respond to them.”

Other researchers on the team were a pair of White’s colleagues at Brown, Linda Resnik and Momotazur Rahman, and Harvard Medical School’s David Grabowski.

McGarry acknowledged the research has been helpful but has left everyone with a “cliff-hanger.”

“The logical question is if anecdotal reports are true that PDPM has been a bit of a pay bump and facilities are able to shed some therapy staff because there are not so many minutes of therapy, or it’s in a group setting, where is the money going? The answer is staying open because of the pandemic [interruption to normal routines]. But that’s something we’re all putting a pin in as researchers.”