More is not always better, especially when talking about the number of employees in a nursing home trying to battle infectious outbreaks such as COVID-19, or even less dangerous annual influenza strains.

That’s a key finding from a new study whose results were released online by Health Affairs on Wednesday.

Certain infection control beliefs and even personal protective equipment levels might not be as important as the volume of workers coming and going at a facility, said lead author Brian McGarry, Ph.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine and the University of Rochester.

“We focused, especially early in the pandemic, on infection control practices in the nursing home and blaming facilities for not following these practices — look no further than the administration program that tied relief payment to COVID outbreak numbers,” McGarry told McKnight’s Long-Term Care News on Wednesday. “But our results indicate these sorts of things mattered a lot less than the amount of staff traffic in and out of facilities for determining COVID outbreak risk. In the absence of daily rapid testing for infected staff, more bodies in a nursing home equaled greater COVID outbreak risk.”

Researchers identified more than 7,000 nursing homes that had no signs of COVID as of June 1, 2020 and then tracked them through September of 2020.

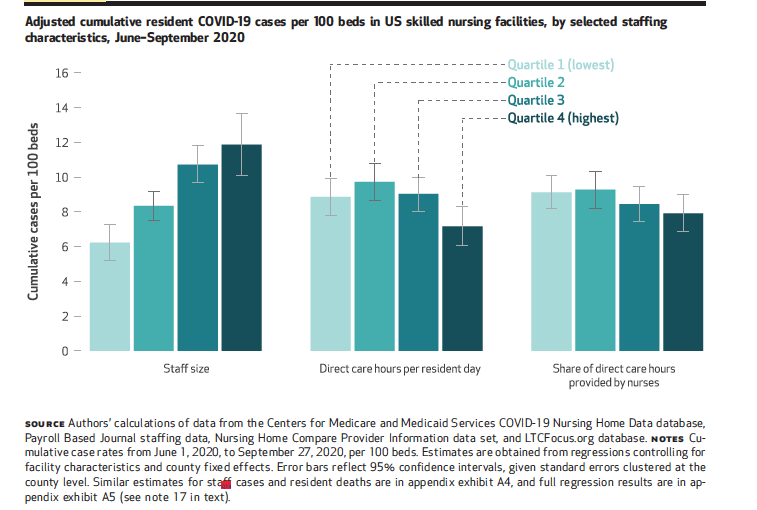

Skilled nursing facilities in the best-performing quartile averaged 6.2 resident cases and 0.9 deaths per 100 beds, compared to double that — 11.9 resident cases and 2.1 deaths per 100 beds — among facilities in the worst quartile.

“The effect was bigger and more robust than we were anticipating,” McGarry said, adding that skill mix and staffing ratios were not significant factors in outcomes. “The magnitude of the results surprised us. It really seemed to swamp the quality-focused component of the staffing story.”

Joining McGarry on the research team were David Grabowski, a professor of healthcare policy at Harvard Medical School; Ashvin Gandhi, an assistant professor at the University of California Los Angeles Anderson School of Management; and Michael Barnett, an assistant professor of health policy and management at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Seeing the overlooked

McGarry said that nursing homes with less dense units — such as Green House models — make more sense with regard to preventing outbreaks. It’s an intuitive finding that wasn’t really being thought about previously, he added.

“Everyone was taking the view that the more staffing you have, the better you’re going to be able to do infection control practices and that if the staff is more highly skilled — more nurses relative to CNAs — they too might be able to better implement infection control,” he explained. “That makes sense from a conceptual standpoint, but our paper shows that those things are on the margin. Something that matters a lot more is just how much traffic you have coming in and out of your facility.”

It’s a simple point, but one that was not considered so much in earlier studies, he said.

“And it was definitely being overlooked in some of the policy responses, like, ‘We have to get them more PPE and incentivize better infection control practices and we have to keep nursing home residents out of communal dining spaces and isolate them in their rooms.’ And all the while you’re doing that, more staff are coming in.”

The introduction of rapid-testing kits in late summer and fall started a turnaround, McGarry believes. That’s when it became easier to screen out asymptomatic and presymptomatic staff and stop them from coming to work.

Broad workforce implications

The focus should remain on staff, McGarry emphasized.

“There’s both the greater investment in staff and paying a living wage so they don’t have to work in multiple facilities, and there’s also the other piece of rethinking how we deliver long-term care and choosing models that are maybe not as cost-effective but provide a better quality of life and have a more controlled environment where you have a better shot at keeping infectious diseases from coming in the door,” he said.

Staff not directly involved in patient care also are key parts of the equation.

“Our findings definitely support that anybody working in a nursing home should be vaccinated,” McGarry said. “That should be a big priority from a policy standpoint: getting as many nursing home workers — even those not involved in direct care: kitchen staff, housekeeping, administrators — vaccinated. The more staff vaccinated, the better protected the homes will likely be.”

Nursing homes employ widely varying staffing levels due to factors such as facility size, layout, services rendered and more, so there is no cookie-cutter recipe for a quick fix. But upgrades should be contemplated, the research team asserts.

“We hope this [study] changes the part of the paradigm we think about infection control and, God forbid, for the next pandemic or for the infectious diseases nursing homes battle on an annual basis,” McGarry said. “It’s somewhat about understanding where the risks are coming from and maybe identifying high vs. low-risk facilities and less about having the nursing home change its staffing pattern overnight, and less about trying to beat the nursing home over the head with penalties for having outbreaks. Because it may be because of things that are sort of out of their control, for better or worse.”