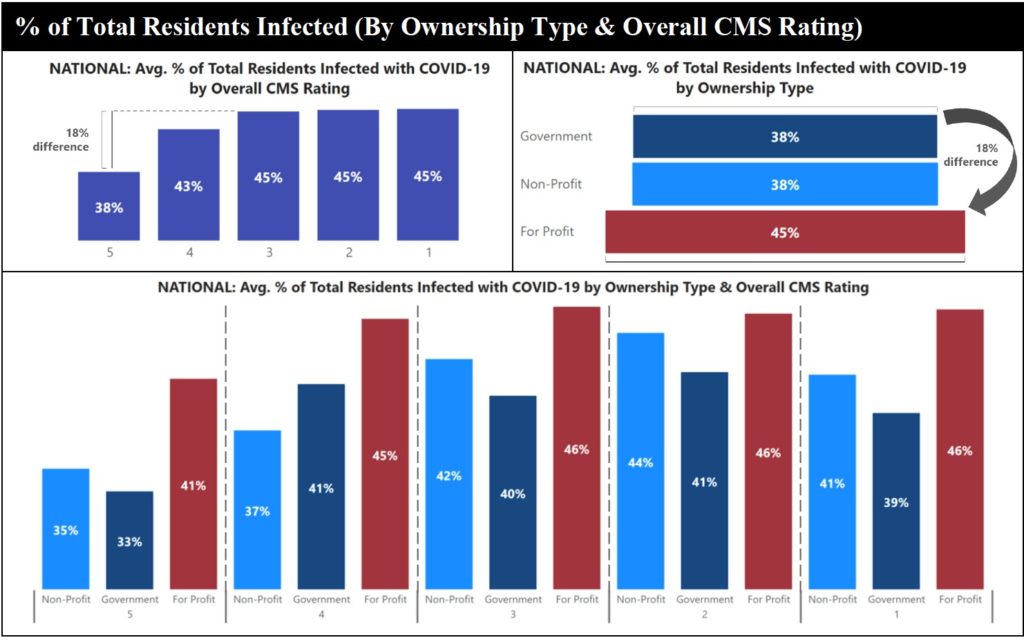

For-profit nursing homes were 18% less effective in controlling COVID-19 infections than nonprofit or government-run facilities in 2020, according to an analysis of federal data published Thursday by a consumer group.

The Center for Medicare Advocacy blasted staffing shortages, lax infection control standards, long-term structural challenges and lack of leadership as being responsible for the industry’s yearlong crisis in “Geography Is Not Destiny: Protecting Nursing Home Residents from the Next Pandemic.” The report calls on regulators to return to a more stringent enforcement approach.

But it also specifically called out profit-driven nursing homes’ alleged failures during the pandemic’s first 10 months in the U.S., arguing that geography — a key when considering community prevalence of COVID-19, according to many researchers — was less a factor in spread than ownership type or staffing.

Using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ COVID-19 dataset and its Care Compare database, the advocacy correlated success in keeping COVID infections at bay with variables including ownership, star ratings, staffing levels and more.

“For-profits were the worst performers across every CMS rating pool,” author Cinnamon St. John said during a webinar hosted by the Center for Medicare Advocacy Thursday.

Facilities of any type with a five-star overall rating, meanwhile, were 18% more effective at preventing COVID infections than facilities with a one-, two- or three-star rating.

“COVID-19 is not an uncontrollable force. It is possible to break this down,” said St. John, associate director of the Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing at NYU and a fellow with the Center for Medicare Advocacy. “There are facilities that have performed well in this crisis.”

During the webinar, Derrick DeWitt, director of the Maryland Baptist Aged Home in Baltimore, shared his approach to pandemic protection, which included forgoing $20,000 of his salary to hire a full-time infection preventionist, staffing a registered nurse on every shift and paying workers for alternative transportation to discourage the use of mass transit.

He said leaders reprioritized spending on infection prevention when they realized it could be “the thing that either made our success or closed us.” Without some financial sacrifices, his small, nonprofit might have gone broke.

DeWitt said Medicaid rates and narrow margins even before COVID-19 made it challenging for many nonprofit nursing homes to institute such practices.

Judith Stein, Center for Medicare Advocacy executive director, argued that for-profit providers also need to consider their margins, but from a different perspective.

“Good care is also good business,” she said, “If entities are in this for a mission, to provide good care … they can give good care (and still) have reasonable success.”

Improvement advice

St. John proposed a series of solutions to “fill the cracks” while waiting for broader fixes for long-standing issues exacerbated by the pandemic. Her report recommends increasing RN staffing, improving wages and benefits for direct care staff, lowering the number of residents allowed per room from the current federal standard of four, and promoting “flexible” leadership.

Infection control practices are a major theme of the study. St. John said the industry needs to build up infrastructure (to include full-time infection preventionists at every building), while the government focuses on enforcing existing rules.

She referenced a May report from the Government Accountability Office that found infection prevention and control deficiencies were the most often cited in nursing homes between 2013 and 2017. Some 82% of facilities docked for a related infraction at least once, and 48% cited in multiple years. Yet only 1% were hit with a financial penalty.

“The problems in infection control were treated as not serious,” said Senior Policy Attorney Toby Edelman. “We know now how wrong that was.”

Edelman also pointed to previous studies as proof that calls for staffing increases were warranted.

A review of all skilled nursing facilities in Connecticut published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society found 20 minutes more direct care per-patient, per-day was associated with a 22% decline in COVID-19 cases.

And in New York, the Office of the Attorney General found that most nursing home COVID-19 deaths occurred at facilities with the lowest tier of direct care staff.

“Of the state’s 401 for-profit facilities, over two-thirds — a total of 280 — entered the COVID-19 pandemic with CMS 1-star or 2-star staffing ratings,” Attorney General Letitia James reported last month. “The OAG found that when controlling for geographic variance among nursing facilities, CMS 5-star staffing rated facilities nonetheless suffered a lower death rate compared to facilities with low CMS staffing ratings.”