Younger nursing home residents, despite dramatically different needs than their older counterparts, have been overlooked by existing efforts to deinstitutionalize care, according to a study published in Health Affairs Monday.

A trio of Harvard University researchers found that long-stay residents under 65 were far more likely to have severe mental illness than their senior counterparts, but those 35 to 64 years old needed far less help with day-to-day care.

Those 20 to 64 also were most likely to live in facilities with lower mean star ratings, owned by for-profit organizations, and in urban settings.

And while SNF use among seniors had fallen in almost all states between 2013 and 2019 due to policy shifts that favor in-home care, the number of younger residents in facilities remained stagnant and even grew in some places.

“Nationally, the rate of nursing home placement of older people with disabilities saw a much faster rate of decline during our study period than that of younger people with disabilities, which — in many states — stagnated or decreased,” wrote the researchers, led by Ari Ne’eman, health policy PhD candidate and disability rights advocate.

Ne’eman’s co-authors included Michael Stein, executive director of the Harvard Law School Project on Disability, and David Grabowski, PhD, healthcare policy professor.

Alaska, Vermont and Orgeon had the lowest use of nursing homes by young people at the end of the study period in 2019; while Missouri, Ohio and Illinois had the highest.

Ne’eman told McKnight’s Long-Term Care News that the inclination to continue pushing younger residents into skilled nursing facilities was in part due to Medicaid’s institutional bias, but also a lack of data that would better inform policy making for a variety of long-term care services and supports.

The long-term trend of declining nursing home use among older adults, he said, obscured the stagnation among young users in many states. But policies that are more supportive of providing alternative care and support for younger patients would improve their quality of life.

“People under the age of 65 make up 15% of nursing home residents, approximately, and often have very different experiences clinically, and also different life experiences,” Ne’eman said. “These are individuals who are often in the nursing home because they have nowhere else to go. The nursing home becomes a provider of last resort. That represents a social policy failure.”

While home- and community-based services covered by Medicaid helped the majority of young people with developmental disabilities transition out of institutional settings, leaving that coverage optional has many young people with severe mental illness or physical disabilities out of luck.

“It obscures the degree to which rebalancing remains very limited among people with other disabilities,” the authors said in their paper.

Ne’eman encouraged the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to desegregate its nursing home long-stay data by age-group, and he also pushed the agency and state leaders to adopt more supportive approaches for young, long-term care patients.

Specifically, Ne’eman said the federal government could begin making clearer the need for more mental health services by revisiting an exemption included in the Preadmission Screening and Resident Review program.

As the law exists now, providers have to screen residents being admitted from an acute-care setting for severe mental illness. It, however, allows providers to skip that step if residents are expected to stay fewer than 30 days for post-acute care. Many end up sliding into long-term stays, Ne’eman said.

To address that exploding need, the authors said CMS should also explore issuing Section 1115 demonstration waivers that permit state Medicaid programs to reimburse for room and board for a targeted population. That would enable more diversions from skilled nursing and could be supplemented by community-based care.

Such an approach could improve equity for the populations most affected, who happen to be largely minority and urban-dwelling in younger age groups.

While 74.6% of older long-stay residents were white, that share fell in each successively younger age group. Black and Hispanic residents made up much higher percentages of younger residents.

“I think all of this is downstream of Medicaid’s institutional bias,” Ne’eman said. “And we know people of color are overrepresented in the under 65 age groups. It’s almost invariably a failure of the safety net.”

Among other new insights into young, long-stay residents:

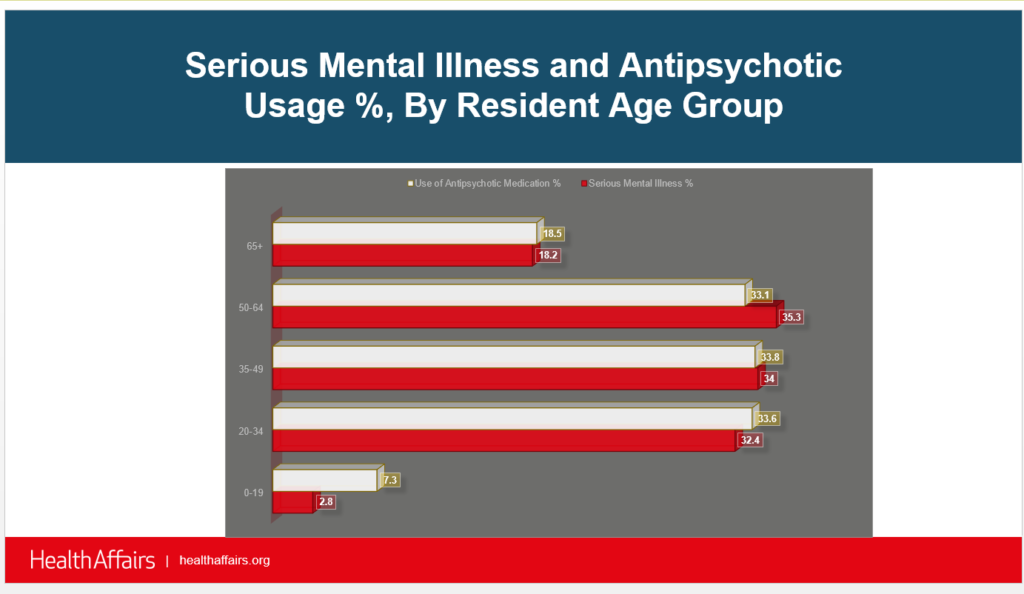

- Younger residents 20 to 64 were almost twice as likely as their older counterparts to use antipsychotic medication.

- Younger residents 20 and older had higher rates of paralysis, traumatic brain injury and multiple sclerosis.

- Residents ages up to age 19 lived in facilities with a mean rating one star higher than the average.