In 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services started focused on-site surveys to address the issue of erroneous coding of schizophrenia in nursing homes.

More recently, the agency began conducting off-site audits to assess the accuracy of Minimum Data Set (MDS) data. They are currently examining nursing homes’ evidence for appropriate documentation, assessment, and coding of residents’ schizophrenia diagnoses.

If CMS identifies inaccuracies in a nursing home’s MDS coding, the facility’s Five-Star rating will be downgraded by one star for six months, which can negatively impact admissions, jeopardize community partnerships, and draw attention from other external stakeholders. However, even more concerning is how these coding problems affect residents.

Inaccurate coding of schizophrenia will result in an improper care plan. Clinicians may improperly ascribe a resident’s acute signs and symptoms to the wrong diagnosis. Future discharges to the community or other care settings will become more difficult for a resident who has been improperly diagnosed.

This has become a top-of-mind issue for providers, or at least should be.

I am presenting a free webinar Tuesday on this very topic together with my mighty colleagues at Zimmet Healthcare Services Group: Alicia Cantinieri, vice president of MDS policy and education, and Melanie Tribe-Scott, director of quality innovations. We will explain the CMS audit plan, review its consequences, and assist facilities in evaluating and mitigating their risk.

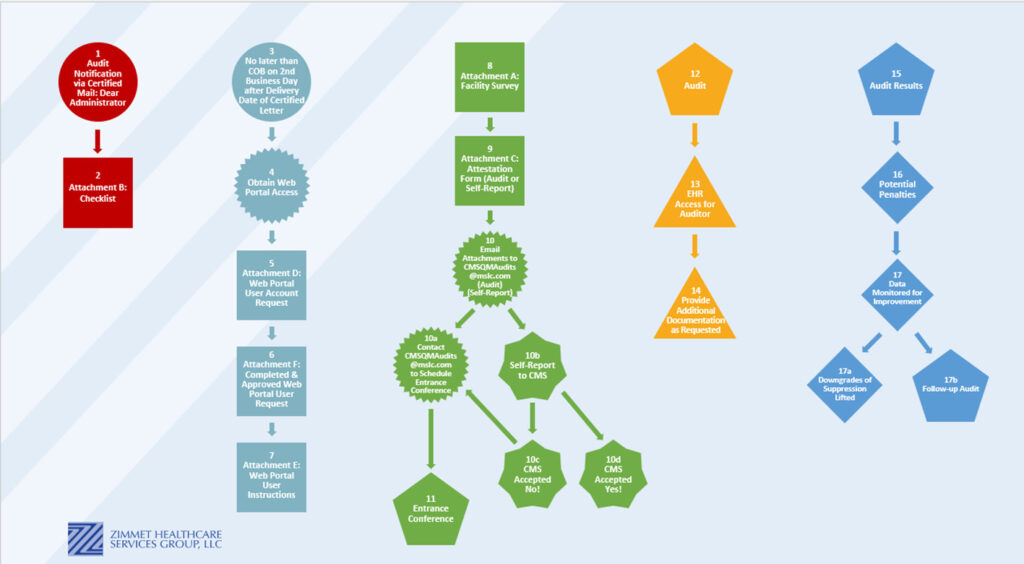

In advance of this webinar, I’d like to share with you this flow diagram that details the new schizophrenia MDS audits (click to enlarge). The diagram was created by reviewing various CMS documents.

It’s difficult to know in advance whether your nursing home will receive the “Dear Administrator” certified letter indicating that you will be audited. However, if you do, that letter will include a detailed checklist outlining what is expected of the facility within two business days. It is essential to have a clear, failure-free process in place to receive and immediately respond to the letter, even during vacations and holidays.

You will be required to immediately set up access to a web portal; the process for doing so is detailed in the letter. Step 9 is key. Here you have to make a decision: 1. schedule the CMS audit, which translates into an attestation statement (attachment C of the letter) that states that you believe your facility’s documentation is appropriate and accurate, or 2. self-report that the documentation is not accurate and submit a corrective action plan. Ultimately, even if you choose the second option, CMS may reject your plan and require the formal audit anyway. To be clear, there is no option to state that your documentation and care is accurate and therefore “don’t audit me.”

“It is possible that a nursing home isn’t aware that they have a problem. So how could you possibly choose to self-report or schedule the CMS audit within two business days?” states Cantinieri. “To be successful, do not wait for a letter. You must immediately conduct an independent audit of those identified on the MDS as having schizophrenia.”

This is not a 10-minute process, Tribe-Scott reminds me. When a resident has I6000 (schizophrenia) indicated on the MDS, we would expect to see a clear indication of that diagnosis in the resident’s medical history, documentation of behaviors, indications of symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions, and documentation of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions. Cantinieri adds: “It is the exception, not the norm, to have a ‘new diagnosis’ of schizophrenia in later life. Review your documentation for the diagnosis as per the RAI Manual instructions under Section I and State Operations Manual guidance.”

If you are audited, CMS will request:

a. MDS assessments at time of admission, the first assessment that was completed with the resident being coded for a schizophrenia diagnosis, and the most recently completed MDS assessment

b. Behavioral health records, including practitioner assessment(s) pertaining to the diagnosis of schizophrenia

c. Medication administration records, progress notes (i.e., gradual dose reduction attempts, etc.), and medication orders pertaining to antipsychotic medication use, if prescribed

d. Other information related to the resident’s schizophrenia diagnosis and antipsychotic medication use, if prescribed

We’ve closely observed the process since the audits have begun. Some providers have had official audits, while others have self-disclosed inaccuracies and submitted plans of correction. Most outcomes from CMS have been the same: Nursing homes with coding inaccuracies had their overall and long-stay quality measure ratings downgraded to one star, thereby lowering the facility’s overall rating by one star. As a result, some facilities dropped out of preferred networks; others received additional scrutiny from external stakeholders.

These consequences, however, are really not the point. Rather, we should be asking ourselves some hard questions: How did we get here? How could any of our facilities manufacture fictitious diagnoses in order to avoid triggering a quality measure? How could we possibly put our residents in potential harm’s way to protect our ratings or continue the use of an unnecessary chemical restraint? It is impossible for me to get my head around this.

Do regulatory sticks and carrots play a role in this behavior? In some states, nursing homes are financially rewarded for low rates of the antipsychotics and antianxiety quality measures, and all facilities are penalized for high rates. The intentions are noble: lower rates of psychotropics. But do these sticks and carrots motivate the wrong behavior?

If you are reading this blog, you are almost certainly doing the right thing. I’m delighted that the majority of the industry is also acting as it should. Yet as the saying goes, a few bad apples do spoil it for the rest of us.

My best advice is to take stock in your own practice. Look inward. If you find problems, do a root cause analysis to ferret out their origins. See you at the webinar, if you can make it.

Steven Littlehale is a gerontological clinical nurse specialist and chief innovation officer at Zimmet Healthcare Services Group.

The opinions expressed in McKnight’s Long-Term Care News guest submissions are the author’s and are not necessarily those of McKnight’s Long-Term Care News or its editors.