While reading through Seema Verma’s recent opinion piece, what caught my eye was her apparent amnesia. So many of her criticisms of the current administration had already existed when she held the reins as administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

It was distracting, and that’s really a shame because she made some excellent observations and identified some solid go-forward strategies.

One of her suggestions, tying reimbursement to investments in quality, is currently done through SNF Value-Based Purchasing (VBP). It’s a good first step, but most providers regard the rewards/penalties as nothing more than “sofa change.”

Some states, like California, have implemented much more significant Medicaid VBP programs that appear to move the needle on quality and feature more than a few coins as a financial upside. However, Ms. Verma also implied (though did not explicitly state) that Five-Star could be the vehicle for this effort. In Five-Star’s current form, this idea simply does not work.

About 20 years ago, I stated from the podium that the best predictor of a facility’s survey outcome was its ZIP code. I didn’t think that I was being controversial or even provocative (OK, maybe a little). Rather, I was making a statement that was clearly outlined in the data and evident to everyone. Right? The correlations between geography, the predominance of resident characteristics (e.g., frailty vs. medical acuity, mental illness and cognitive impairment vs. unimpaired), and survey outcomes continue to be as high today as they’ve been over my last two decades of study.

This means that if you care for an atypical population or happen to be in certain places in a state, your survey outcomes will likely be worse.

The Quality Indicator Survey (QIS) was intended to make the survey process more data driven and objective, but has it? Ms. Verma stated, “The top 10 most frequently cited deficiencies have been consistent for the past 10 years, meaning the inspection process has made no impact on keeping nursing homes adherent to regulations.” She’s correct, but maybe it’s time to look at the regulations and how we determine compliance and deficiency. I also continue to find little to no correlation between survey and quality measure outcomes.

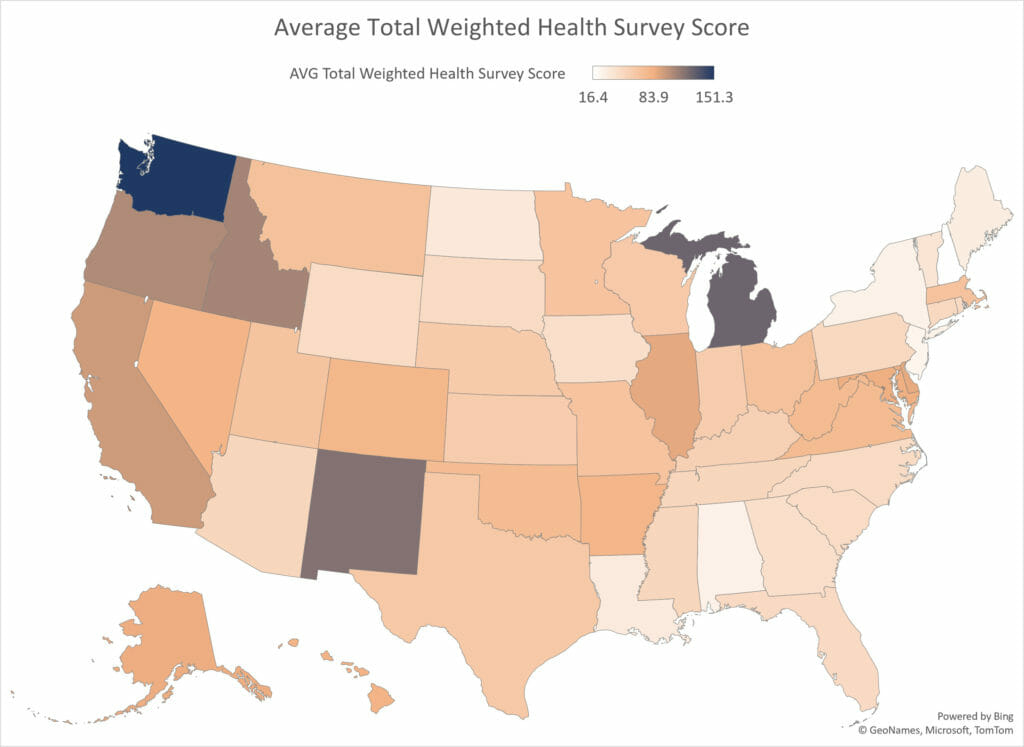

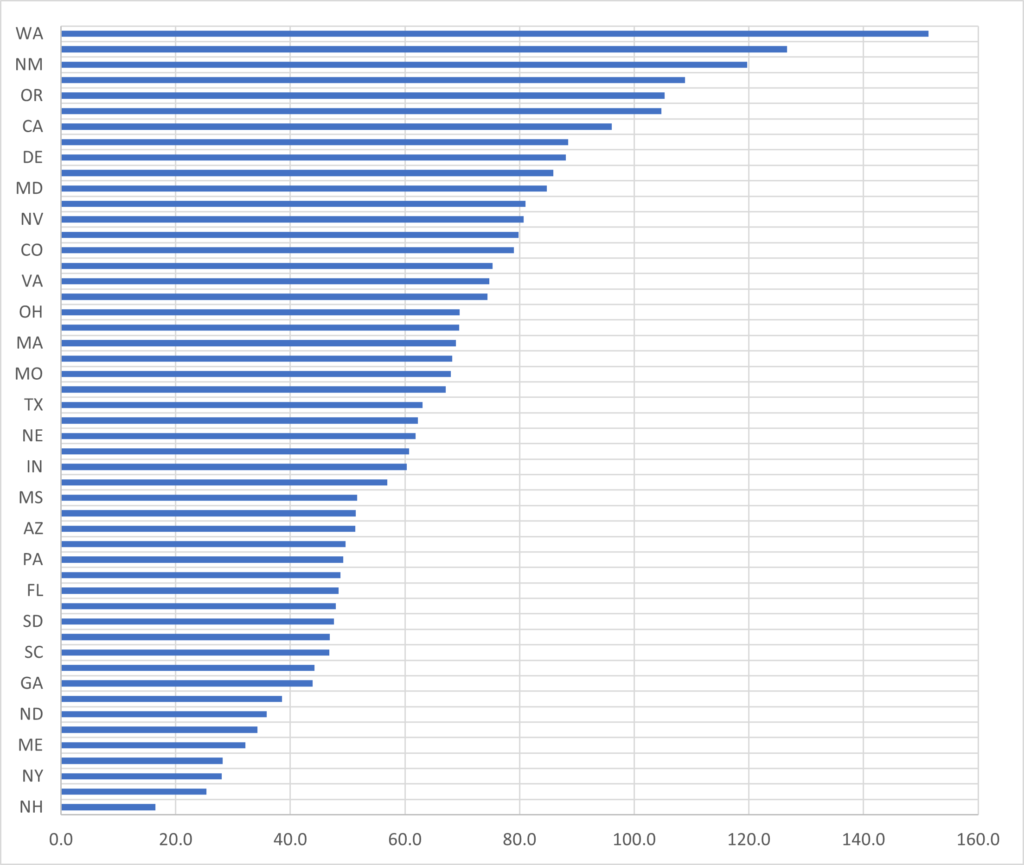

Students of Five-Star (and those who aspire to be) know that CMS makes good efforts to “level the playing field” and address the disparities between survey outcomes in different regions. “Nonetheless there remains variation among states in both inspection process and outcomes,” CMS states in its Technical Users’ Guide for Five-Star. Here you see a wide interstate dispersion in survey outcomes as measured by average health inspection score.

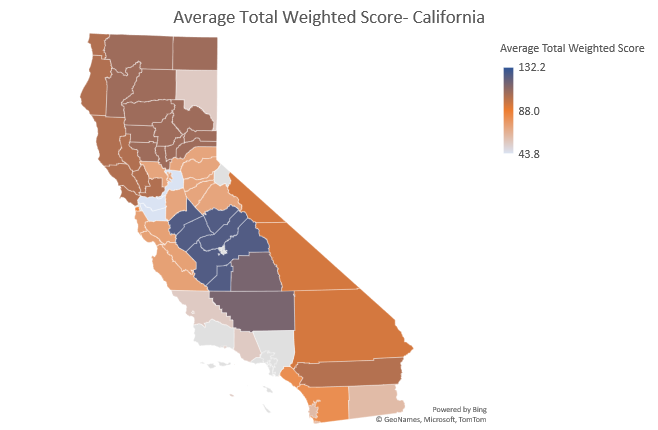

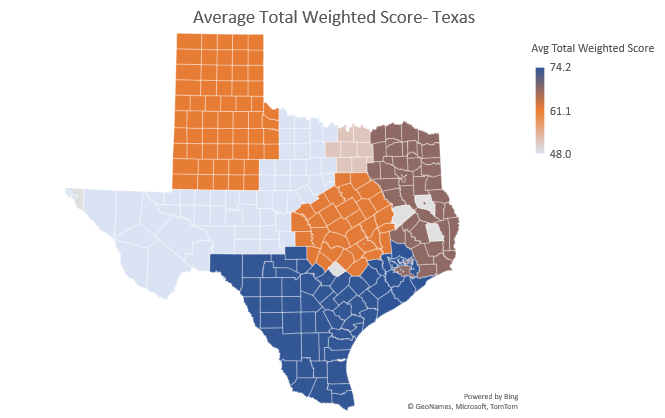

As mentioned, Five-Star attempts to control for this by comparing nursing homes within the same state when calculating a health inspection rating. But consider the following examples of California, Texas and Florida. Why is there such a range in survey outcomes across state survey districts?

Before considering any go-forward strategies, can we address the fundamentally broken survey process? How can we possibly link one more initiative to Five-Star when geography is such a strong predictor of survey success?

Our nation’s elders, and those who devote their lives to caring for them, would benefit greatly if we moved beyond the partisan political rhetoric and toward developing authentic strategies that measurably reform the care in U.S. nursing homes.

Steven Littlehale is a gerontological clinical nurse specialist and chief innovation officer at Zimmet Healthcare Services Group.

The opinions expressed in McKnight’s Long-Term Care News guest submissions are the author’s and are not necessarily those of McKnight’s Long-Term Care News or its editors.