It’s never been more important to listen to your frontline workers in emergencies.

Managers need to trust them when they offer advice or concerns, and supervisors need to know what their staff is thinking.

At the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, nursing homes and congregate healthcare facilities were one of the most dangerous workplaces in the country. Nursing home employees’ deaths ranked among the highest of any job in the United States.

Today certified nursing assistants are asking, “will anything change?”

People working in these facilities were in more danger of being infected with the virus than in any other workplace. In nursing homes, the virus aggressively attacked the workers, and nursing assistants were directly in the line of fire. Yet, ordered to remain on their job in the face of death, many remained unwavering. These workers should not be forgotten.

Take, for example, Tanya, a Connecticut CNA with 23 years of experience whose story was reported by Time in May 2020. She began showing symptoms of COVID but only had a low-grade fever, not the 100.4 degrees the facility required before sending staff home. Her request for time off was denied, and she continued to work with inadequate PPE. She later tested positive for COVID, potentially putting both residents and fellow employees at risk.

“The worst thing that I get upset about is hearing the word hero, hero, hero being thrown around for us. And no one is treating us as such. We feel disrespected,” Tanya told Time.

Maurice, a CNA who had spent 25 years working at one Austin, TX, long-term care facility, posted on Facebook during the early days of the pandemic, “I can’t stay home… I am a healthcare worker.” He died from COVID just weeks later. Maurice was the type of worker who treated every one of his assigned residents with kindness and respect and made sure each was comfortable prior to ending his shift. CNAs like him deserve better.

Many of these workers felt unsafe and left their jobs, and without a different perspective on training, the staffing crisis will become catastrophic. Surely 2022 and beyond can’t be the same.

I contracted the virus from a coworker and was hospitalized. This was the worst experience of my life, and I was determined to break the chain of infection. My dilemma was not to infect others nor become reinfected with the virus.

These thoughts continued to haunt me before returning to work. There was no manual on what to do after leaving work, nor a decontamination station from work to home. My first defense was to test twice monthly, followed by a blood test for active antibodies every three months. This was done regardless of vaccination status. I wasn’t comfortable returning to work without a new facility contingency plan.

In order not to repeat the same mistakes again, why not ask a CNA or other frontline worker what needs to be done? Here are a few suggestions that may help.

- Trust us concerning safety protocols. We are more informed about the realities of our workplace safety.

- Training — Employees need thorough training focused on the facility’s contingency plans to protect the residents and keep employees up-to-date about safety protocols.

- Testing should be the only requirement related to staffing during pandemic and epidemic crises.

- Term-limits — A nursing assistant’s certification should be a life certificate instead of a recertification every two years.

- Recruiting and retention should remain at emergency COVID-19 status.

- A reserve staffing force should be implemented.

The lack of staffing is critical. Without proper staffing levels, our other contingency plans will be ineffective, and we will lose this war… again.

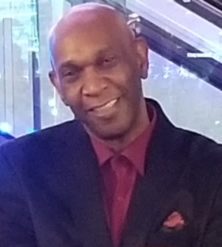

John Booker is a nursing assistant and healthcare worker with 40 years of industry experience, focused on serving as an advocate for healthcare workers in America.

The opinions expressed in McKnight’s Long-Term Care News guest submissions are the author’s and are not necessarily those of McKnight’s Long-Term Care News or its editors.